The Rainbow Portrait of Queen Elizabeth I

The Rainbow Portrait of Queen Elizabeth

I,

Attributed to Isaac Oliver (1556–1617)

Attributed to Marcus Gheeraerts (II) (1561–1636)

link

Her headdress is an incredible design

decorated lavishly

with pearls and rubies and supports her royal crown. The

pearls symbolize her virginity; the crown, of course, symbolizes

her royalty. Pearls also adorn the transparent veil which hangs

over her shoulders. Above her crown is a crescent-shaped jewel

which alludes to Cynthia, the goddess of the moon

link

The eyes and ears painted into the

fabric of

dress in the Rainbow Portrait clearly imply a sense of

omniscience; as queen, she was able to hear and see all.

link

thus allowing the queen to pose in the guise of Astraea, the

virginal heroine of classical literature

link

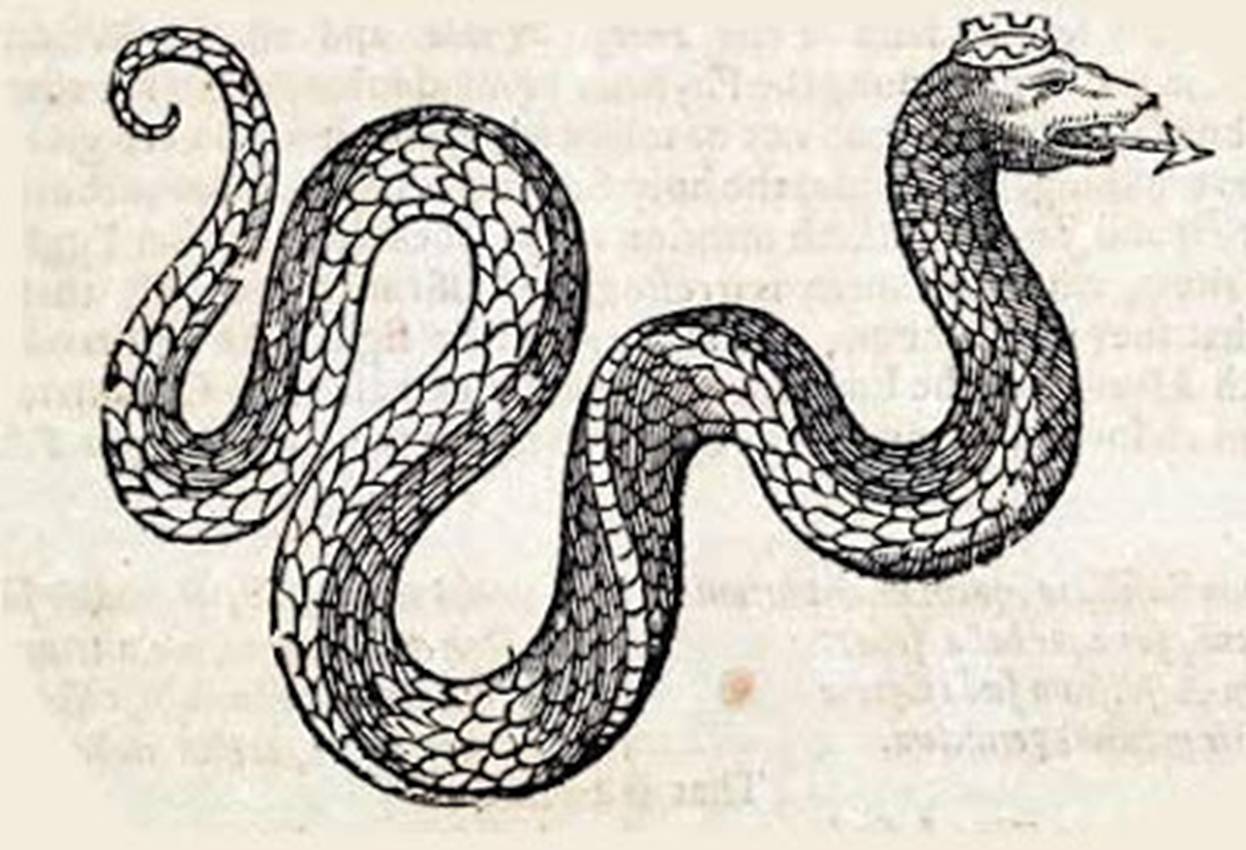

A jeweled serpent is entwined along her

left arm,

and holds from its mouth a heart-shaped ruby. Above

its head is a celestial sphere. The serpent symbolizes wisdom;

it has captured the ruby, which in turn symbolizes the

queen's heart. In other words, the queen's passions

are controlled by her wisdom

link

Cockatrice snake serpent

http://polarbearstale.blogspot.fr/2012/06/rainbow-portrait-of-queen-elizabeth-i.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elizabeth_I_of_England

Elizabeth I of

England

From Wikipedia,

the free encyclopedia

"Elizabeth

I", "Elizabeth of England", and "Elizabeth Tudor"

redirect here. For other uses, see Elizabeth I (disambiguation), Elizabeth of England (disambiguation), and Elizabeth Tudor (disambiguation).

|

Elizabeth I |

|

|

Elizabeth I , "Darnley

Portrait", c. 1575 |

|

|

Queen of

England and Ireland (more...) |

|

|

Reign |

17 November 1558 – 24 March 1603 |

|

15 January 1559 |

|

|

Predecessors |

|

|

Successor |

|

|

|

|

|

Father |

|

|

Mother |

|

|

Born |

|

|

Died |

|

|

Burial |

|

|

Signature |

|

|

Religion |

|

Elizabeth I (7

September 1533 – 24 March 1603) was queen regnant of England and Ireland from

17 November 1558 until her death. Sometimes called "The Virgin Queen",

"Gloriana" or "Good Queen Bess", Elizabeth

was the fifth and last monarch of the Tudor dynasty.

The daughter of Henry VIII, she was born a princess, but

her mother, Anne Boleyn,

was executed two and a half years after her birth, and Elizabeth was declared

illegitimate. Her half-brother, Edward VI, bequeathed the crown to Lady Jane Grey,

cutting his two half-sisters, Elizabeth and the Catholic Mary,

out of the succession in spite of statute law to the contrary. His will was

set aside, Mary became queen, and Lady Jane Grey was executed. In 1558,

Elizabeth succeeded her half-sister, during whose reign she had been imprisoned

for nearly a year on suspicion of supporting Protestant rebels.

Elizabeth set out to rule by good counsel,[1] and she depended heavily on a group of

trusted advisers led byWilliam Cecil, Baron Burghley. One of her

first moves as queen was the establishment of an English Protestant church, of

which she became the Supreme Governor. This Elizabethan Religious Settlement later evolved into today's Church of

England. It was expected that Elizabeth would marry and produce an

heir so as to continue the Tudor line. She never did, however, despite numerous

courtships. As she grew older, Elizabeth became famous for her virginity, and a

cult grew up around her which was celebrated in the portraits, pageants, and

literature of the day.

In government, Elizabeth was more moderate

than her father and half-siblings had been.[2] One of her mottoes was "video

et taceo" ("I see, and say nothing").[3] In religion she was relatively

tolerant, avoiding systematic persecution. After 1570, when the pope declared

her illegitimate and released her subjects from obedience to her, several

conspiracies threatened her life. All plots were defeated, however, with the

help of her ministers' secret service. Elizabeth was cautious in foreign

affairs, moving between the major powers of France and Spain. She only

half-heartedly supported a number of ineffective, poorly resourced military

campaigns in the Netherlands, France, and Ireland. In the mid-1580s, war with

Spain could no longer be avoided, and when Spain finally decided to attempt to

conquer England in 1588, the failure of the Spanish Armada associated her with one of the

greatest victories in English history.

Elizabeth's reign is known as the Elizabethan era,

famous above all for the flourishing of English drama, led by playwrights such as William Shakespeare and Christopher Marlowe, and for the seafaring

prowess of English adventurers such as Sir Francis

Drake. Some historians are more reserved in their assessment. They

depict Elizabeth as a short-tempered, sometimes indecisive ruler,[4] who enjoyed more than her share of

luck. Towards the end of her reign, a series of economic and military problems

weakened her popularity. Elizabeth is acknowledged as a charismatic performer and a dogged survivor, in an

age when government was ramshackle and limited and when monarchs in

neighbouring countries faced internal problems that jeopardised their thrones.

Such was the case with Elizabeth's rival, Mary, Queen of Scots, whom she imprisoned

in 1568 and eventually had executed in 1587. After the short reigns of

Elizabeth's half-siblings, her 44 years on the throne provided welcome

stability for the kingdom and helped forge a sense of national identity.[2]

Contents

[hide] o

7.1 Mary and the Catholic cause o

8.3 Supporting Henry IV of France o

8.6 Barbary states, Ottoman Empire ·

10 Death ·

14 Notes o

16.1 Primary sources and early histories |

Early life

Elizabeth

was the only child of Henry VIIIand Anne Boleyn,

who did not bear a male heir and was executed less than three years after

Elizabeth's birth.

Elizabeth was born at Greenwich Palace and was named after both her

grandmothers, Elizabeth of

York andElizabeth Howard.[5] She was the second child of Henry VIII of England born in wedlock to survive infancy.

Her mother was Henry's second wife, Anne Boleyn.

At birth, Elizabeth was the heiress presumptive to the throne of England. Her older

half-sister, Mary,

had lost her position as a legitimate heir when Henry annulled his marriage to

Mary's mother, Catherine of Aragon, in order to marry

Anne and sire a male heir to ensure the Tudor succession.[6][7] Elizabeth was baptised on 10

September; Archbishop

Thomas Cranmer, the Marquess of Exeter, the Duchess of Norfolk and the Dowager Marchioness of Dorset stood as her four godparents.

When Elizabeth was two years and eight months

old, her mother was executed on 19 May 1536.[8] Elizabeth was declared illegitimate

and deprived of the title of princess.[9] Eleven days after Anne Boleyn's death,

Henry marriedJane Seymour, but she died shortly after the birth of their

son, Prince Edward, in 1537. From his birth,

Edward was undisputed heir apparent to the throne. Elizabeth was placed in his

household and carried the chrisom, or baptismal

cloth, at his christening.[10]

The

Lady Elizabeth in about 1546, by an unknown artist

Elizabeth's first Lady Mistress, Margaret Bryan,

wrote that she was "as toward a child and as gentle of conditions as ever

I knew any in my life".[11] By the autumn of 1537, Elizabeth was

in the care of Blanche Herbert, Lady Troy,

who remained her Lady Mistress until her retirement in late 1545 or early 1546.[12] Catherine Champernowne, better known by

her later, married name of Catherine "Kat" Ashley, was appointed as

Elizabeth's governess in 1537, and she remained Elizabeth's friend until her

death in 1565, when Blanche Parry succeeded her as Chief Gentlewoman of

the Privy Chamber.[13] Champernowne taught Elizabeth four

languages: French, Flemish,

Italian and Spanish.[14]By

the time William Grindal became her tutor in 1544, Elizabeth could write

English, Latin, and Italian. Under

Grindal, a talented and skilful tutor, she also progressed in French and Greek.[15] After Grindal died in 1548, Elizabeth

received her education under Roger Ascham,

a sympathetic teacher who believed that learning should be engaging.[16] By the time her formal education ended

in 1550, she was one of the best educated women of her generation.[17] By the end of her life, Elizabeth was

also reputed to speak Welsh, Cornish, Scottish and Irish in addition to English. The

Venetian ambassador stated in 1603 that she "possessed [these] languages

so thoroughly that each appeared to be her native tongue".[18] Historian Mark Stoyle suggests that

she was probably taught Cornish by William Killigrew, Groom

of the Privy Chamber and later Chamberlain of the Exchequer.[19]

Thomas Seymour

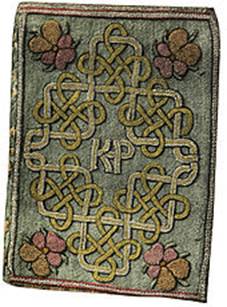

The Miroir or Glasse of the Synneful

Soul, a translation from the French, by

Elizabeth, presented to Catherine Parr in 1544. The embroidered binding with

the monogram KP for "Katherine Parr" is believed to have been worked

by Elizabeth.[20]

Henry VIII died in 1547; Elizabeth's

half-brother, Edward VI, became king at age nine. Catherine Parr,

Henry's widow, soon married Thomas Seymour of Sudeley,

Edward VI's uncle and the brother of the Lord Protector, Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset. The

couple took Elizabeth into their household at Chelsea.

There Elizabeth experienced an emotional crisis that some historians believe

affected her for the rest of her life.[21] Seymour, approaching age 40 but having

charm and "a powerful sex appeal",[21] engaged in romps and horseplay with

the 14-year-old Elizabeth. These included entering her bedroom in his

nightgown, tickling her and slapping her on the buttocks. Parr, rather than

confront her husband over his inappropriate activities, joined in. Twice she

accompanied him in tickling Elizabeth, and once held her while he cut her black

gown "into a thousand pieces."[22] However, after Parr discovered the

pair in an embrace, she ended this state of affairs.[23]In

May 1548, Elizabeth was sent away.

However, Thomas Seymour continued scheming to

control the royal family and tried to have himself appointed the governor of

the King's person.[24][25] When Parr died after childbirth on 5

September 1548, he renewed his attentions towards Elizabeth, intent on marrying

her.[26] The details of his former behaviour

towards Elizabeth emerged,[27] and for his brother and the council,

this was the last straw.[28] In January 1549, Seymour was arrested

on suspicion of plotting to marry Elizabeth and overthrow his brother.

Elizabeth, living at Hatfield House,

would admit nothing. Her stubbornness exasperated her interrogator, Sir Robert

Tyrwhitt, who reported, "I do see it in her face that she is guilty".[28] Seymour was beheaded on 20 March 1549.

Mary I's reign

Mary I,

by Anthonis Mor,

1554

Edward VI died on 6 July 1553, aged 15. His will

swept aside the Succession to the Crown Act 1543, excluded

both Mary and Elizabeth from the succession, and instead declared as his heir Lady Jane Grey,

granddaughter of Henry VIII's sister Mary, Duchess of Suffolk. Lady Jane was

proclaimed queen by the Privy Council, but her support quickly crumbled, and

she was deposed after nine days. Mary rode triumphantly into London, with

Elizabeth at her side.[29]

The show of solidarity between the sisters

did not last long. Mary, a devout Catholic, was determined to crush the

Protestant faith in which Elizabeth had been educated, and she ordered that

everyone attend Catholic Mass; Elizabeth had to outwardly conform. Mary's

initial popularity ebbed away in 1554 when she announced plans to marry Prince Philip of Spain, the son of Emperor Charles V and an active Catholic.[30] Discontent spread rapidly through the

country, and many looked to Elizabeth as a focus for their opposition to Mary's

religious policies.

In January and February 1554, Wyatt's rebellion broke out; it was soon suppressed.[31] Elizabeth was brought to court, and

interrogated regarding her role, and on 18 March, she was imprisoned in the Tower of London.

Elizabeth fervently protested her innocence.[32] Though it is unlikely that she had

plotted with the rebels, some of them were known to have approached her. Mary's

closest confidant, Charles V's ambassador Simon Renard,

argued that her throne would never be safe while Elizabeth lived; and the

Chancellor, Stephen Gardiner,

worked to have Elizabeth put on trial.[33] Elizabeth's supporters in the

government, including Lord Paget, convinced Mary to spare her

sister in the absence of hard evidence against her. Instead, on 22 May,

Elizabeth was moved from the Tower to Woodstock, where she was to spend almost a

year under house arrest in the charge of Sir Henry Bedingfield. Crowds cheered her

all along the way.[34][35]

The

remaining wing of the Old Palace,Hatfield House.

It was here that Elizabeth was told of her sister's death in November 1558.

On 17 April 1555, Elizabeth was recalled to

court to attend the final stages of Mary's apparent pregnancy. If Mary and her

child died, Elizabeth would become queen. If, on the other hand, Mary gave

birth to a healthy child, Elizabeth's chances of becoming queen would recede

sharply. When it became clear that Mary was not pregnant, no one believed any

longer that she could have a child.[36] Elizabeth's succession seemed assured.[37]

King Philip, who ascended the Spanish throne

in 1556, acknowledged the new political reality and cultivated his

sister-in-law. She was a better ally than the chief alternative, Mary, Queen of Scots, who had grown up in

France and was betrothed to the Dauphin of France.[38] When his wife fell ill in 1558, King

Philip sent the Count of Feria to consult with Elizabeth.[39] This interview was conducted at

Hatfield House, where she had returned to live in October 1555. By October

1558, Elizabeth was already making plans for her government. On 6 November,

Mary recognised Elizabeth as her heir.[40] On 17 November 1558, Mary died and

Elizabeth succeeded to the throne.

Accession

Elizabeth became queen at the age of 25, and

declared her intentions to her Council and other peers who had come to Hatfield

to swear allegiance. The speech contains the first record of her adoption of

the mediaeval political theology of the sovereign's "two

bodies": the body natural and the body politic:[41]

Elizabeth

I in her coronation robes, patterned with Tudor roses and trimmed with ermine.

My lords, the law of nature moves me to

sorrow for my sister; the burden that is fallen upon me makes me amazed, and

yet, considering I am God's creature, ordained to obey His appointment, I will

thereto yield, desiring from the bottom of my heart that I may have assistance

of His grace to be the minister of His heavenly will in this office now

committed to me. And as I am but one body naturally considered, though by His

permission a body politic to govern, so shall I desire you all ... to be

assistant to me, that I with my ruling and you with your service may make a

good account to Almighty God and leave some comfort to our posterity on earth.

I mean to direct all my actions by good advice and counsel.[42]

As her triumphal

progress wound through

the city on the eve of the coronation ceremony, she was welcomed

wholeheartedly by the citizens and greeted by orations and pageants, most with

a strong Protestant flavour. Elizabeth's open and gracious responses endeared

her to the spectators, who were "wonderfully ravished".[43] The following day, 15 January 1559,

Elizabeth was crowned and anointed by Owen Oglethorpe,

the Catholic bishop of Carlisle, at Westminster

Abbey. She was then presented for the people's acceptance, amidst a

deafening noise of organs, fifes, trumpets, drums, and bells.[44]

Church settlement

Main

article: Elizabethan Religious Settlement

Elizabeth's personal religious convictions

have been much debated by scholars. She was a Protestant, but kept Catholic

symbols (such as the crucifix), and downplayed the role of sermons in defiance

of a key Protestant belief.[45]

In terms of public policy she favoured

pragmatism in dealing with religious matters. The question of her legitimacy

was a key concern: Although she was technically illegitimate under both

Protestant and Catholic law, her retroactively declared illegitimacy under the

English church was not a serious bar compared to having never been legitimate

as the Catholics claimed she was. For this reason alone, it was never in

serious doubt that Elizabeth would embrace Protestantism.

Elizabeth and her advisors perceived the

threat of a Catholic crusade against heretical England. Elizabeth therefore

sought a Protestant solution that would not offend Catholics too greatly while

addressing the desires of English Protestants; she would not tolerate the more

radical Puritans though, who were pushing for

far-reaching reforms.[46] As a result, the parliament of 1559

started to legislate for a church based on the Protestant settlement of Edward VI, with

the monarch as its head, but with many Catholic elements, such as priestly

vestments.[47]

The House of Commons backed the proposals strongly, but the

bill of supremacy met opposition in the House of Lords,

particularly from the bishops. Elizabeth was fortunate that many bishoprics

were vacant at the time, including the Archbishopric of Canterbury.[48][49] This enabled supporters amongst peers

to outvote the bishops and conservative peers. Nevertheless, Elizabeth was

forced to accept the title of Supreme Governor of the Church of

England rather than

the more contentious title of Supreme Head,

which many thought unacceptable for a woman to bear. The new Act of Supremacy became law on 8 May 1559. All public

officials were to swear an oath of loyalty to the monarch as the supreme

governor or risk disqualification from office; the heresy laws were repealed, to avoid a repeat

of the persecution of dissenters practised by Mary. At the same time, a new Act of Uniformity was passed, which made attendance at

church and the use of an adapted version of the 1552 Book of Common Prayer compulsory, though the penalties for recusancy, or failure to

attend and conform, were not extreme.[50]

Marriage question

Elizabeth

and her favourite, Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester,

c. 1575. Pair of stamp-sized miniatures by Nicholas

Hilliard.[51] The Queen's friendship with Dudley

lasted for over thirty years, until his death.

From the start of Elizabeth's reign, it was

expected that she would marry and the question arose to whom. She never did,

although she received many offers for her hand; the reasons for this are not

clear. Historians have speculated that Thomas Seymour had put her off sexual

relationships, or that she knew herself to be infertile.[52][53]She

considered several suitors until she was about fifty. Her last courtship was

with Francis, Duke of Anjou, 22 years her

junior. While risking possible loss of power like her sister, who played into

the hands of King Phillip II of Spain, marriage offered the chance of an heir.[54] However, the choice of a husband might

also provoke political instability or even insurrection.[55]

Robert Dudley

In the spring of 1559 it became evident that

Elizabeth was in love with her childhood friend Robert Dudley.[56] It was said that Amy Robsart,

his wife, was suffering from a "malady in one of her breasts", and

that the Queen would like to marry Dudley if his wife should die.[57] By the autumn of 1559 several foreign

suitors were vying for Elizabeth's hand; their impatient envoys engaged in ever

more scandalous talk and reported that a marriage with her favouritewas not welcome

in England:[58] "There is not a man who does not

cry out on him and her with indignation ... she will marry none but the

favoured Robert".[59] Amy Dudley died in September 1560 from

a fall from a flight of stairs and, despite the coroner's inquest finding of accident, many people

suspected Dudley to have arranged her death so that he could marry the queen.[60] Elizabeth seriously considered

marrying Dudley for some time. However, William Cecil, Nicholas Throckmorton, and some

conservative peers made

their disapproval unmistakably clear.[61] There were even rumours that the

nobility would rise if the marriage took place.[62]

Among other marriages being considered for

the queen, Robert Dudley was regarded as a possible candidate for nearly

another decade.[63] Elizabeth was extremely jealous of his

affections, even when she no longer meant to marry him herself.[64] In 1564 Elizabeth raised Dudley to the

peerage as Earl of

Leicester. He finally remarried in 1578, to which the queen reacted

with repeated scenes of displeasure and lifelong hatred towards his wife.[65] Still, Dudley always "remained at

the centre of [Elizabeth's] emotional life", as historian Susan Doran has described the situation.[66] He died shortly after the defeat of theArmada.

After Elizabeth's own death, a note from him was found among her most personal

belongings, marked "his last letter" in her handwriting.[67]

Political aspects

Francis, Duke of Anjou, byNicholas

Hilliard. Elizabeth called the duke her "frog", finding

him "not so deformed" as she had been led to expect.[68]

Marriage negotiations constituted a key

element in Elizabeth's foreign policy.[69] She turned down Philip II's own hand in 1559, and negotiated for

several years to marry his cousin Archduke Charles of Austria. By 1569,

relations with the Habsburgs had deteriorated, and Elizabeth considered

marriage to two French Valois princes in turn, first Henry, Duke of Anjou, and later, from 1572

to 1581, his brother Francis, Duke of Anjou, formerly Duke of

Alençon.[70] This last proposal was tied to a

planned alliance against Spanish control of the Southern Netherlands.[71] Elizabeth seems to have taken the

courtship seriously for a time, and wore a frog-shaped earring that Anjou had

sent her.[72]

In 1563, Elizabeth told an imperial envoy:

"If I follow the inclination of my nature, it is this: beggar-woman and

single, far rather than queen and married".[69] Later in the year, following

Elizabeth's illness with smallpox, the succession

question became a heated issue in Parliament. They urged the queen to marry or

nominate an heir, to prevent a civil war upon her death. She refused to do

either. In April she prorogued the Parliament, which did not

reconvene until she needed its support to raise taxes in 1566. Having promised

to marry previously, she told an unruly House:

I will never break the word of a prince

spoken in public place, for my honour's sake. And therefore I say again, I will

marry as soon as I can conveniently, if God take not him away with whom I mind

to marry, or myself, or else some other great let happen.[73]

By 1570, senior figures in the government

privately accepted that Elizabeth would never marry or name a successor.

William Cecil was already seeking solutions to the succession problem.[69] For her failure to marry, Elizabeth

was often accused of irresponsibility.[74] Her silence, however, strengthened her

own political security: she knew that if she named an heir, her throne would be

vulnerable to a coup; she remembered that the way "a second person, as I

have been" had been used as the focus of plots against her predecessor.[75]

The

"Hampden" portrait, by Steven van der Meulen, ca. 1563. This is

the earliest full-length portrait of the queen, made before the emergence of

symbolic portraits representing the iconography of the "Virgin Queen".[76]

Elizabeth's unmarried status inspired a cult

of virginity. In poetry and portraiture, she was depicted as a virgin or a

goddess or both, not as a normal woman.[77] At first, only Elizabeth made a virtue

of her virginity: in 1559, she told the Commons, "And, in the end, this

shall be for me sufficient, that a marble stone shall declare that a queen,

having reigned such a time, lived and died a virgin".[78] Later on, poets and writers took up

the theme and turned it into an iconography that exalted Elizabeth. Public

tributes to the Virgin by 1578 acted as a coded assertion of opposition to the

queen's marriage negotiations with the Duke of Alençon.[79]

Putting a positive spin on her marital

status, Elizabeth insisted she was married to her kingdom and subjects, under

divine protection. In 1599, she spoke of "all my husbands, my good

people".[80]

Mary,

Queen of Scots

Elizabeth's first policy toward Scotland was

to oppose the French presence there.[81] She feared that the French planned to

invade England and put Mary, Queen of Scots, who was considered

by many to be the heir to the English crown,[82] on the throne.[83] Elizabeth was persuaded to send a

force into Scotland to aid the Protestant rebels, and though the campaign was

inept, the resulting Treaty of Edinburgh of July 1560 removed the French threat

in the north.[84] When Mary returned to Scotland in 1561

to take up the reins of power, the country had an established Protestant church

and was run by a council of Protestant nobles supported by Elizabeth.[85] Mary refused to ratify the treaty.[86]

In 1563 Elizabeth proposed her own suitor,

Robert Dudley, as a husband for Mary, without asking either of the two people

concerned. Both proved unenthusiastic,[87] and in 1565 Mary married Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley, who carried

his own claim to the English throne. The marriage was the first of a series of

errors of judgement by Mary that handed the victory to the Scottish Protestants

and to Elizabeth. Darnley quickly became unpopular in Scotland and then

infamous for presiding over the murder of Mary's Italian secretary David Rizzio.

In February 1567, Darnley was murdered by conspirators almost certainly led by James Hepburn, Earl of Bothwell. Shortly

afterwards, on 15 May 1567, Mary married Bothwell, arousing suspicions that she

had been party to the murder of her husband. Elizabeth wrote to her:

How could a worse choice be made for your

honour than in such haste to marry such a subject, who besides other and

notorious lacks, public fame has charged with the murder of your late husband,

besides the touching of yourself also in some part, though we trust in that

behalf falsely.[88]

These events led rapidly to Mary's defeat and

imprisonment in Loch Leven

Castle. The Scottish lords forced her to abdicate in favour of her

son James, who had been born in June 1566.

James was taken to Stirling Castle to be raised as a Protestant. Mary

escaped from Loch Leven in 1568 but after another defeat fled

across the border into England, where she had once been assured of support from

Elizabeth. Elizabeth's first instinct was to restore her fellow monarch; but

she and her council instead chose to play safe. Rather than risk returning Mary

to Scotland with an English army or sending her to France and the Catholic

enemies of England, they detained her in England, where she was imprisoned for

the next nineteen years.[89]

Mary and the Catholic cause

Sir Francis Walsingham, Principal Secretary 1573–1590. Being Elizabeth'sspymaster, he uncovered

several plots against her life.

Mary was soon the focus for rebellion. In

1569 there was a major Catholic rising in the North; the goal was to free

Mary, marry her to Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk, and

put her on the English throne.[90] After the rebels' defeat, over 750 of

them were executed on Elizabeth's orders.[91] In the belief that the revolt had been

successful,Pope Pius V issued

a bull in 1570, titled Regnans in Excelsis, which declared

"Elizabeth, the pretended Queen of England and the servant of crime"

to be excommunicate and a heretic, releasing all her

subjects from any allegiance to her.[92][93] Catholics who obeyed her orders were

threatened with excommunication.[92] The papal bull provoked legislative

initiatives against Catholics by Parliament, which were however mitigated by

Elizabeth's intervention.[94] In 1581, to convert English subjects

to Catholicism with "the intent" to withdraw them from their

allegiance to Elizabeth was made a treasonable

offence, carrying the death penalty.[95] From the 1570s missionary

priests from

continentalseminaries came to England secretly in the cause

of the "reconversion of England".[93] Many suffered execution, engendering a

cult of martyrdom.[93]

Regnans in Excelsis gave

English Catholics a strong incentive to look to Mary Stuart as the true

sovereign of England. Mary may not have been told of every Catholic plot to put

her on the English throne, but from the Ridolfi Plot of 1571 (which caused Mary's suitor,

the Duke of Norfolk, to lose his head) to the Babington Plot of 1586, Elizabeth's spymaster Sir Francis Walsingham and the royal council keenly assembled

a case against her.[96] At first, Elizabeth resisted calls for

Mary's death. By late 1586 she had been persuaded to sanction her trial and

execution on the evidence of letters written during the Babington Plot.[97] Elizabeth's proclamation of the

sentence announced that "the said Mary, pretending title to the same

Crown, had compassed and imagined within the same realm divers things tending

to the hurt, death and destruction of our royal person."[98] On 8 February 1587, Mary was beheaded

at Fotheringhay Castle, Northamptonshire.[99] After Mary's execution, Elizabeth

claimed not to have ordered it and indeed most accounts have her telling

Secretary Davidson, who brought her the warrant to sign, not to dispatch the

warrant even though she had signed it. The sincerity of Elizabeth's remorse and

her motives for telling Davidson not to execute the warrant have been called

into question both by her contemporaries and later historians.

Wars

and overseas trade

Half Groat of Elizabeth I

Elizabeth's foreign policy was largely

defensive. The exception was the English occupation of Le Havre from October 1562 to June 1563, which

ended in failure when Elizabeth's Huguenot allies joined with the Catholics to

retake the port. Elizabeth's intention had been to exchange Le Havre for Calais, lost to France in

January 1558.[100] Only through the activities of her

fleets did Elizabeth pursue an aggressive policy. This paid off in the war

against Spain, 80% of which was fought at sea.[101] She knighted Francis Drake after his circumnavigation of the globe from 1577 to 1580, and he

won fame for his raids on Spanish ports and fleets. An element of piracy and self-enrichment drove Elizabethan

seafarers, over which the queen had little control.[102][103]

Netherlands expedition

After the occupation and loss of Le Havre in 1562–1563, Elizabeth avoided

military expeditions on the continent until 1585, when she sent an English army

to aid the Protestant Dutch rebels against Philip II.[104] This followed the deaths in 1584 of

the allies William the Silent, Prince of Orange, and Francis, Duke of Anjou, and the surrender

of a series of Dutch towns to Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma, Philip's

governor of the Spanish Netherlands. In December 1584, an

alliance between Philip II and the French Catholic League at Joinville undermined the ability of Anjou's

brother, Henry III of France, to counter Spanishdomination

of the Netherlands. It also extended Spanish influence along the channel coast of France, where the Catholic

League was strong, and exposed England to invasion.[104] The siege of Antwerp in the summer of 1585 by the Duke of

Parma necessitated some reaction on the part of the English and the Dutch. The

outcome was the Treaty of

Nonsuch of August

1585, in which Elizabeth promised military support to the Dutch.[105] The treaty marked the beginning of the Anglo-Spanish War, which lasted until the Treaty of London in 1604.

The expedition was led by her former suitor,

Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester. Elizabeth from the start did not really back

this course of action. Her strategy, to support the Dutch on the surface with

an English army, while beginning secret peace talks with Spain within days of

Leicester's arrival in Holland,[106] had necessarily to be at odds with

Leicester's, who wanted and was expected by the Dutch to fight an active campaign.

Elizabeth on the other hand, wanted him "to avoid at all costs any

decisive action with the enemy".[107] He enraged Elizabeth by accepting the

post of Governor-General from the Dutch States-General. Elizabeth saw this as a

Dutch ploy to force her to accept sovereignty over the Netherlands,[108] which so far she had always declined.

She wrote to Leicester:

We could never have imagined (had we not seen

it fall out in experience) that a man raised up by ourself and extraordinarily

favoured by us, above any other subject of this land, would have in so

contemptible a sort broken our commandment in a cause that so greatly touches

us in honour....And therefore our express pleasure and commandment is that, all

delays and excuses laid apart, you do presently upon the duty of your

allegiance obey and fulfill whatsoever the bearer hereof shall direct you to do

in our name. Whereof fail you not, as you will answer the contrary at your

utmost peril.[109]

Elizabeth's "commandment" was that

her emissary read out her letters of disapproval publicly before the Dutch

Council of State, Leicester having to stand nearby.[110] This public humiliation of her

"Lieutenant-General" combined with her continued talks for a separate

peace with Spain,[111] irreversibly undermined his standing

among the Dutch. The military campaign was severely hampered by Elizabeth's

repeated refusals to send promised funds for her starving soldiers. Her

unwillingness to commit herself to the cause, Leicester's own shortcomings as a

political and military leader and the faction-ridden and chaotic situation of

Dutch politics were reasons for the campaign's failure.[112] Leicester finally resigned his command

in December 1587.

Spanish Armada

Meanwhile, Sir Francis Drake had undertaken a major voyage against

Spanish ports and ships to the Caribbean in 1585 and 1586, and in 1587 had made

asuccessful raid on Cadiz, destroying the

Spanish fleet of war ships intended for the Enterprise

of England:[113] Philip II had decided to take the war

to England.[114]

Portrait

of Elizabeth to commemorate the defeat of theSpanish Armada (1588), depicted in the background.

Elizabeth's hand rests on the globe, symbolising her international power.

On 12 July 1588, the Spanish Armada,

a great fleet of ships, set sail for the channel, planning to ferry a Spanish

invasion force under the Duke of Parma to the coast of southeast England from

the Netherlands. A combination of miscalculation,[115] misfortune, and an attack of English fire ships on 29 July off Gravelines which dispersed the Spanish ships to the northeast defeated the

Armada.[116]The

Armada straggled home to Spain in shattered remnants, after disastrous losses

on the coast of Ireland (after some ships had tried to struggle back to Spain

via the North Sea,

and then back south past the west coast of Ireland).[117] Unaware of the Armada's fate, English

militias mustered to defend the country under the Earl of Leicester's command.

He invited Elizabeth to inspect her troops atTilbury in Essex on 8 August. Wearing a silver

breastplate over a white velvet dress, she addressed them in one of her most famous speeches:

My loving people, we have been persuaded by

some that are careful of our safety, to take heed how we commit ourself to

armed multitudes for fear of treachery; but I assure you, I do not desire to

live to distrust my faithful and loving people ... I know I have the body but

of a weak and feeble woman, but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of

a King of England too, and think foul scorn that Parma or Spain, or any Prince

of Europe should dare to invade the borders of my realm.[118]

When no invasion came, the nation rejoiced.

Elizabeth's procession to a thanksgiving service at St Paul's Cathedral rivalled that of her coronation as a

spectacle.[117] The defeat of the armada was a potent

propaganda victory, both for Elizabeth and for Protestant England. The English

took their delivery as a symbol of God's favour and of the nation's

inviolability under a virgin queen.[101] However, the victory was not a turning

point in the war, which continued and often favoured Spain.[119] The Spanish still controlled the

Netherlands, and the threat of invasion remained.[114] Sir Walter Raleigh claimed after her death that

Elizabeth's caution had impeded the war against Spain:

If the late queen would have believed her men

of war as she did her scribes, we had in her time beaten that great empire in

pieces and made their kings of figs and oranges as in old times. But her

Majesty did all by halves, and by petty invasions taught the Spaniard how to

defend himself, and to see his own weakness.[120]

Though some historians have criticised

Elizabeth on similar grounds,[121] Raleigh's verdict has more often been

judged unfair. Elizabeth had good reason not to place too much trust in her

commanders, who once in action tended, as she put it herself, "to be

transported with an haviour of vainglory".[122]

Supporting Henry IV of France

Coat of arms of Queen Elizabeth I, with her

personal motto: "Semper

eadem" or "always

the same"

When the Protestant Henry IV inherited

the French throne in 1589, Elizabeth sent him military support. It was her

first venture into France since the retreat from Le Havre in 1563. Henry's

succession was strongly contested by the Catholic League and by Philip II, and Elizabeth feared

a Spanish takeover of the channel ports. The subsequent English campaigns in

France, however, were disorganised and ineffective.[123] Lord Willoughby, largely

ignoring Elizabeth's orders, roamed northern France to little effect, with an

army of 4,000 men. He withdrew in disarray in December 1589, having lost half

his troops. In 1591, the campaign of John Norreys,

who led 3,000 men to Brittany, was even more of

a disaster. As for all such expeditions, Elizabeth was unwilling to invest in

the supplies and reinforcements requested by the commanders. Norreys left for

London to plead in person for more support. In his absence, a Catholic League

army almost destroyed the remains of his army at Craon, north-west France, in

May 1591. In July, Elizabeth sent out another force under Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, to help

Henry IV in besieging Rouen. The result was just

as dismal. Essex accomplished nothing and returned home in January 1592. Henry

abandoned the siege in April.[124] As usual, Elizabeth lacked control

over her commanders once they were abroad. "Where he is, or what he doth,

or what he is to do," she wrote of Essex, "we are ignorant".[125]

Ireland

Main

article: Tudor conquest of Ireland

Although Ireland was one of her two kingdoms,

Elizabeth faced a hostile, and in places virtually autonomous,[126] Irish population that adhered to

Catholicism and was willing to defy her authority and plot with her enemies.

Her policy there was to grant land to her courtiers and prevent the rebels from

giving Spain a base from which to attack England.[127] In the course of a series of

uprisings, Crown forces pursued scorched-earth tactics, burning the land and

slaughtering man, woman and child. During a revolt in Munster led by Gerald FitzGerald, Earl of Desmond,

in 1582, an estimated 30,000 Irish people starved to death. The poet and

colonist Edmund Spenser wrote that the victims "were

brought to such wretchedness as that any stony heart would have rued the

same".[128]Elizabeth

advised her commanders that the Irish, "that rude and barbarous

nation", be well treated; but she showed no remorse when force and

bloodshed were deemed necessary.[129]

Between 1594 and 1603, Elizabeth faced her

most severe test in Ireland during the Nine Years' War, a revolt that took place

at the height of hostilities withSpain, who backed the rebel leader, Hugh O'Neill, Earl of Tyrone.[130] In spring 1599, Elizabeth sent Robert Devereux,

2nd Earl of Essex, to put the revolt down. To her frustration,[131] he made little progress and returned

to England in defiance of her orders. He was replaced by Charles Blount, Lord Mountjoy, who took

three years to defeat the rebels. O'Neill finally surrendered in 1603, a few

days after Elizabeth's death.[132] Soon afterwards, a peace treaty was

signed between England and Spain.

Russia

Ivan the

Terrible shows his

treasures to Elizabeth's ambassador. Painting by Alexander Litovchenko, 1875

Elizabeth continued to maintain the

diplomatic relations with the Tsardom of

Russia originally

established by her deceased brother. She often wrote to its then ruler, Tsar Ivan IV, on amicable

terms, though the Tsar was often annoyed by her focus on commerce rather than

on the possibility of a military alliance. The Tsar even proposed to her once,

and during his later reign, asked for a guarantee to be granted asylum in

England should his rule be jeopardised. Upon Ivan's death, he was succeeded by

his simple-minded son Feodor. Unlike his father, Feodor had no

enthusiasm in maintaining exclusive trading rights with England. Feodor

declared his kingdom open to all foreigners, and dismissed the English

ambassador Sir Jerome Bowes,

whose pomposity had been tolerated by the new Tsar's late father. Elizabeth

sent a new ambassador, Dr. Giles Fletcher, to demand from the regent Boris Godunov that he convince the Tsar to

reconsider. The negotiations failed, due to Fletcher addressing Feodor with two

of his titles omitted. Elizabeth continued to appeal to Feodor in half

appealing, half reproachful letters. She proposed an alliance, something which

she had refused to do when offered one by Feodor's father, but was turned down.[133]

Barbary states, Ottoman Empire

Abd el-Ouahed ben Messaoud,Moorish ambassador of theBarbary States to the Court of Queen Elizabeth I in

1600.[134]

Trade and diplomatic relations developed

between England and the Barbary states during the rule of Elizabeth.[135][136]England

established a trading relationship with Morocco in opposition to Spain, selling

armour, ammunition, timber, and metal in exchange for Moroccan sugar, in spite

of a Papal ban.[137] In 1600, Abd el-Ouahed ben Messaoud, the principal

secretary to the Moroccan ruler Mulai Ahmad

al-Mansur, visited England as an ambassador to the court of queen

Elizabeth I,[135][138] in order to negotiate an Anglo-Moroccan alliance against Spain.[134][135] Elizabeth "agreed to sell

munitions supplies to Morocco, and she and Mulai Ahmad al-Mansur talked on and

off about mounting a joint operation against the Spanish".[139] Discussions however remained

inconclusive, and both rulers died within two years of the embassy.[140]

Diplomatic relations were also established with

the Ottoman Empire with the chartering of the Levant Company and the dispatch of the first English

ambassador to the Porte, William Harborne,

in 1578.[139] For the first time, a Treaty of

Commerce was signed in 1580.[141] Numerous envoys were dispatched in

both directions and epistolar exchanges occurred between Elizabeth and Sultan Murad III.[139] In one correspondence, Murad

entertained the notion that Islam and Protestantism had "much more in common than

either did with Roman Catholicism, as both rejected the worship of idols",

and argued for an alliance between England and the Ottoman Empire.[142] To the dismay of Catholic Europe,

England exported tin and lead (for cannon-casting) and ammunitions to the

Ottoman Empire, and Elizabeth seriously discussed joint military operations

with Murad III during the outbreak of war with Spain

in 1585, as Francis Walsingham was lobbying for a direct Ottoman military

involvement against the common Spanish enemy.[143]

Later years

Portrait

of Elizabeth I attributed to Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger or his studio, ca. 1595.

The period after the defeat of the Spanish

Armada in 1588 brought new difficulties for Elizabeth that lasted the fifteen

years until the end of her reign.[119] The conflicts with Spain and in

Ireland dragged on, the tax burden grew heavier, and the economy was hit by

poor harvests and the cost of war. Prices rose and the standard of living fell.[144][145]During

this time, repression of Catholics intensified, and Elizabeth authorised

commissions in 1591 to interrogate and monitor Catholic householders.[146] To maintain the illusion of peace and

prosperity, she increasingly relied on internal spies and propaganda.[144] In her last years, mounting criticism

reflected a decline in the public's affection for her.[147]

One of the causes for this "second

reign" of Elizabeth, as it is sometimes called,[148] was the different character of

Elizabeth's governing body, the privy council in the 1590s. A new generation was in

power. With the exception of Lord Burghley, the most important politicians had

died around 1590: The Earl of Leicester in 1588, Sir Francis Walsingham in

1590, Sir Christopher Hatton in 1591.[149] Factional strife in the government,

which had not existed in a noteworthy form before the 1590s,[150] now became its hallmark.[151] A bitter rivalry between the Earl

of Essex andRobert Cecil, son of Lord Burghley, and

their respective adherents, for the most powerful positions in the state marred

politics.[152] The queen's personal authority was

lessening,[153] as is shown in the affair of Dr.

Lopez, her trusted physician. When he was wrongly accused by the Earl of Essex of treason out of personal pique, she

could not prevent his execution, although she had been angry about his arrest

and seems not to have believed in his guilt (1594).[154]

Elizabeth, during the last years of her

reign, came to rely on granting monopolies as a cost-free system of patronage

rather than ask Parliament for more subsidies in a time of war.[155] The practice soon led to price-fixing,

the enrichment of courtiers at the public's expense, and widespread resentment.[156] This culminated in agitation in the

House of Commons during the parliament of 1601.[157] In her famous "Golden Speech"

of 30 November 1601, Elizabeth professed ignorance of the abuses and won the

members over with promises and her usual appeal to the emotions:[158]

Who keeps their sovereign from the lapse of

error, in which, by ignorance and not by intent they might have fallen, what

thank they deserve, we know, though you may guess. And as nothing is more dear

to us than the loving conservation of our subjects' hearts, what an undeserved

doubt might we have incurred if the abusers of our liberality, the thrallers of

our people, the wringers of the poor, had not been told us![159]

Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, byWilliam Segar,

1588

This same period of economic and political

uncertainty, however, produced an unsurpassed literary flowering in England.[160] The first signs of a new literary

movement had appeared at the end of the second decade of Elizabeth's reign,

with John Lyly's Euphues and Edmund Spenser's The Shepheardes Calender in 1578. During the 1590s, some of the

great names of English literature entered their maturity, including William Shakespeare and Christopher Marlowe. During this period

and into the Jacobean era that followed, the English theatre

reached its highest peaks.[161] The notion of a great Elizabethan age depends largely on the builders,

dramatists, poets, and musicians who were active during Elizabeth's reign. They

owed little directly to the queen, who was never a major patron of the arts.[162]

As Elizabeth aged her image gradually

changed. She was portrayed as Belphoebe or Astraea, and after the Armada, as Gloriana, the eternally

youthful Faerie Queene of Edmund Spenser's

poem. Her painted portraits became less realistic and more a set of enigmatic icons that made her look much younger than

she was. In fact, her skin had been scarred by smallpox in 1562, leaving her half bald and

dependent on wigs and cosmetics.[163] Sir Walter Raleigh called her "a

lady whom time had surprised".[164] However, the more Elizabeth's beauty

faded, the more her courtiers praised it.[163]

Elizabeth was happy to play the part,[165] but it is possible that in the last

decade of her life she began to believe her own performance. She became fond

and indulgent of the charming but petulant young Robert Devereux, Earl of

Essex, who was Leicester's stepson and took liberties with her for which she

forgave him.[166] She repeatedly appointed him to

military posts despite his growing record of irresponsibility. After Essex's

desertion of his command in Ireland in 1599, Elizabeth had him placed under

house arrest and the following year deprived him of his monopolies.[167] In February 1601, the earl tried to

raise a rebellion in London. He intended to seize the queen but few rallied to

his support, and he was beheaded on 25 February. Elizabeth knew that her own

misjudgements were partly to blame for this turn of events. An observer

reported in 1602 that "Her delight is to sit in the dark, and sometimes

with shedding tears to bewail Essex".[168]

Death

Elizabeth

I. The "Rainbow Portrait", c. 1600, an allegorical representation of the Queen, become

ageless in her old age

Elizabeth's senior advisor, Burghley, died on 4 August 1598. His political

mantle passed to his son, Robert Cecil, who soon became the leader

of the government.[169] One task he addressed was to prepare

the way for a smooth succession. Since Elizabeth would never name her

successor, Cecil was obliged to proceed in secret.[170] He therefore entered into a coded negotiation with James VI of Scotland, who had a strong but

unrecognised claim.[171]Cecil

coached the impatient James to humour Elizabeth and "secure the heart of

the highest, to whose sex and quality nothing is so improper as either needless

expostulations or over much curiosity in her own actions".[172] The advice worked. James's tone

delighted Elizabeth, who responded: "So trust I that you will not doubt

but that your last letters are so acceptably taken as my thanks cannot be

lacking for the same, but yield them to you in grateful sort".[173] In historian J. E. Neale's view,

Elizabeth may not have declared her wishes openly to James, but she made them

known with "unmistakable if veiled phrases".[174]

The Queen's health remained fair until the

autumn of 1602, when a series of deaths among her friends plunged her into a

severe depression. In February 1603, the death of Catherine Howard, Countess of

Nottingham, the niece of her cousin and close friend Catherine, Lady Knollys, came as a

particular blow. In March, Elizabeth fell sick and remained in a "settled

and unremovable melancholy".[175] She died on 24 March 1603 at Richmond Palace,

between two and three in the morning. A few hours later, Cecil and the council

set their plans in motion and proclaimedJames VI of Scotland as king of England.[176]

Elizabeth's coffin was carried downriver at

night to Whitehall, on a barge lit with torches. At

her funeral on 28 April, the coffin was taken to Westminster

Abbey on a hearse drawn by four horses hung with black

velvet. In the words of the chronicler John Stow:

Westminster was surcharged with multitudes of

all sorts of people in their streets, houses, windows, leads and gutters, that

came out to see the obsequy, and when they

beheld her statue lying upon the coffin, there was such a general sighing,

groaning and weeping as the like hath not been seen or known in the memory of

man.[177]

Elizabeth's

funeral cortège, 1603, with banners of her royal ancestors

Elizabeth was interred in Westminster Abbey

in a tomb she shares with her half-sister, Mary. The Latin inscription on their

tomb, "Regno consortes & urna, hic obdormimus Elizabetha et Maria

sorores, in spe resurrectionis", translates to "Consorts in realm and

tomb, here we sleep, Elizabeth and Mary, sisters, in hope of resurrection".[178]

Legacy and memory

Further

information: Cultural depictions of Elizabeth I of

England

Elizabeth was lamented by many of her

subjects, but others were relieved at her death.[179]Expectations

of King James started high but then declined, so by the 1620s there was a

nostalgic revival of the cult of Elizabeth.[180] Elizabeth was praised as a heroine of

the Protestant cause and the ruler of a golden age. James was depicted as a

Catholic sympathiser, presiding over a corrupt court.[181] The triumphalist image that Elizabeth

had cultivated towards the end of her reign, against a background of

factionalism and military and economic difficulties,[182] was taken at face value and her

reputation inflated. Godfrey Goodman,

Bishop of Gloucester, recalled: "When we had experience of a Scottish

government, the Queen did seem to revive. Then was her memory much magnified."[183] Elizabeth's reign became idealised as

a time when crown, church and parliament had worked in constitutional balance.[184]

Elizabeth

I, painted after 1620, during the first revival of interest in her reign. Time

sleeps on her right and Death looks over her left shoulder; two putti hold the crown above her head.[185]

The picture of Elizabeth painted by her

Protestant admirers of the early 17th century has proved lasting and

influential.[186] Her memory was also revived during the Napoleonic Wars,

when the nation again found itself on the brink of invasion.[187] In the Victorian era,

the Elizabethan legend was adapted to the imperial ideology of the day,[179][188] and in the mid-20th century, Elizabeth

was a romantic symbol of the national resistance to foreign threat.[189][190] Historians of that period, such as J. E. Neale (1934) and A. L. Rowse (1950), interpreted Elizabeth's reign

as a golden age of progress.[191] Neale and Rowse also idealised the

Queen personally: she always did everything right; her more unpleasant traits

were ignored or explained as signs of stress.[192]

Recent historians, however, have taken a more

complicated view of Elizabeth.[193] Her reign is famous for the defeat of

the Armada, and for successful raids against the Spanish, such as those on

Cádiz in 1587 and 1596, but some historians point to military failures on land

and at sea.[123] In Ireland, Elizabeth's forces

ultimately prevailed, but their tactics stain her record.[194] Rather than as a brave defender of the

Protestant nations against Spain and the Habsburgs, she is more often regarded

as cautious in her foreign policies. She offered very limited aid to foreign

Protestants and failed to provide her commanders with the funds to make a

difference abroad.[195]

Elizabeth established an English church that

helped shape a national identity and remains in place today.[196][197][198] Those who praised her later as a

Protestant heroine overlooked her refusal to drop all practices of Catholic

origin from the Church of England.[199] Historians note that in her day,

strict Protestants regarded the Acts of Settlement and Uniformity of 1559 as a compromise.[200][201] In fact, Elizabeth believed that faith

was personal and did not wish, as Francis Bacon put it, to "make windows into

men's hearts and secret thoughts".[202][203]

Though Elizabeth followed a largely defensive

foreign policy, her reign raised England's status abroad. "She is only a

woman, only mistress of half an island," marvelled Pope Sixtus V, "and yet

she makes herself feared by Spain, by France, by the Empire,

by all".[204] Under Elizabeth, the nation gained a

new self-confidence and sense of sovereignty, as Christendom fragmented.[180][205][206] Elizabeth was the first Tudor to

recognise that a monarch ruled by popular consent.[207] She therefore always worked with

parliament and advisers she could trust to tell her the truth—a style of

government that her Stuart successors failed to follow. Some historians have

called her lucky;[204] she believed that God was protecting

her.[208] Priding herself on being "mere

English",[209] Elizabeth trusted in God, honest

advice, and the love of her subjects for the success of her rule.[210] In a prayer, she offered thanks to God

that:

[At a time] when wars and seditions with

grievous persecutions have vexed almost all kings and countries round about me,

my reign hath been peacable, and my realm a receptacle to thy afflicted Church.

The love of my people hath appeared firm, and the devices of my enemies

frustrate.[204]

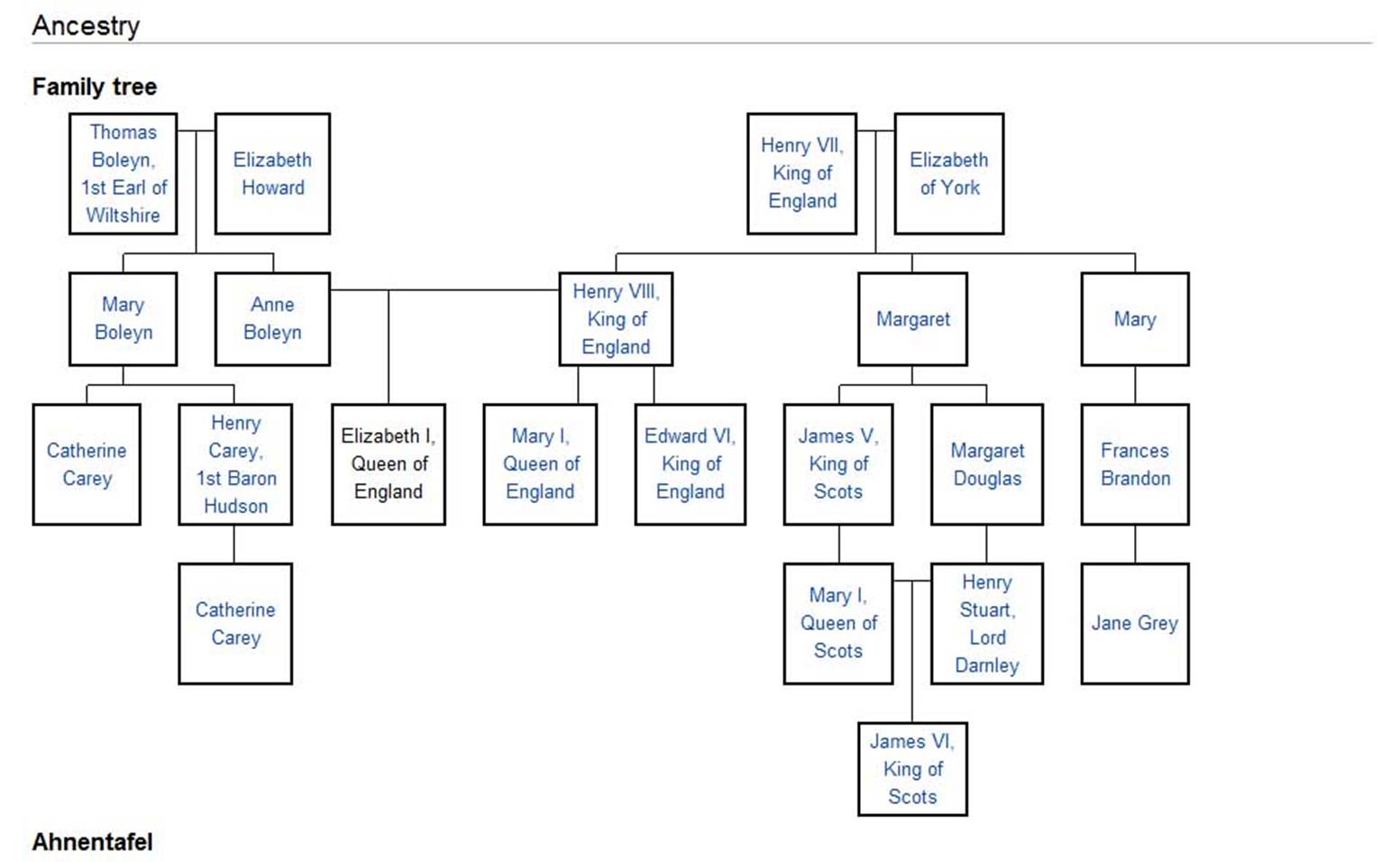

Ancestry

Charles I of

England

From Wikipedia,

the free encyclopedia

|

Charles I |

|

|

Portrait by Anthony van Dyck, 1636 |

|

|

King of England and Ireland (more...) |

|

|

Reign |

27 March 1625 – |

|

2 February 1626 |

|

|

Predecessor |

|

|

Successor |

Charles II (de jure) |

|

Reign |

27 March 1625 – |

|

Coronation |

18 June 1633 |

|

Predecessor |

|

|

Successor |

|

|

|

|

|

Spouse |

|

|

Issue |

|

|

Charles II |

|

|

Father |

|

|

Mother |

|

|

Born |

19 November 1600 |

|

Died |

30 January 1649 (aged 48) |

|

Burial |

7 February 1649 |

|

Religion |

|

Charles I (19

November 1600 – 30 January 1649) was King of England, King of Scotland, and King of Ireland from

27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649.[a] Charles engaged in a struggle for

power with the Parliament of England, attempting to

obtain royal revenue whilst the Parliament sought to curb his Royal

prerogative which

Charles believed was divinely ordained. Many of his English

subjects opposed his actions, in particular his interference in the English and

Scottish churches and the levying of taxes without parliamentary consent,

because they saw them as those of a tyrannical, absolute monarch.[1]

Charles's reign was also

characterised by religious conflicts. His failure to successfully aid

Protestant forces during the Thirty Years' War, coupled with the fact

that he married a Roman Catholic princess,[2][3] generated deep mistrust concerning the

king's dogma. Charles further

allied himself with controversial ecclesiastic figures, such asRichard Montagu and William Laud,

whom Charles appointed Archbishop of Canterbury. Many of

Charles's subjects felt this brought the Church of

England too close to

the Roman Catholic Church. Charles's later attempts to force religious reforms

upon Scotland led to the Bishops' Wars,

strengthened the position of the English and Scottish parliaments and helped

precipitate his own downfall.

Charles's last years were

marked by the English Civil

War, in which he fought the forces of the English and Scottish

parliaments, which challenged his attempts to overrule and negate parliamentary

authority, whilst simultaneously using his position as head of the English

Church to pursue religious policies which generated the antipathy of reformed groups such as the Puritans. Charles was

defeated in the First Civil War (1642–45), after which Parliament expected him

to accept its demands for a constitutional monarchy. He instead remained

defiant by attempting to forge an alliance with Scotland and escaping to the Isle of Wight.

This provoked the Second Civil War (1648–49) and a second defeat for Charles,

who was subsequently captured, tried, convicted, and executed for high treason.

The monarchy was then abolished and a republic

called the Commonwealth of England, also referred to

as the Cromwellian Interregnum, was declared.

Charles's son, Charles II, who dated his accession from

the death of his father, did not take up the reins of government until the restoration of the monarchy in 1660.[1]

Contents

[hide] ·

8 Trial ·

11 Titles, styles, honours and arms ·

13 Issue ·

15 Notes |

[edit]Early life

[edit]Second son

The second son of James VI of

Scotland and Anne of Denmark,

Charles was born in Dunfermline Palace, Fife, on 19 November 1600.[1][4] His paternal grandmother was Mary, Queen of Scots. Charles was baptised

on 2 December 1600 by the Bishop of Ross, in a ceremony held in Holyrood Abbey,

and was created Duke of Albany, Marquess of Ormond, Earl of Ross and Lord Ardmannoch.[5]

Charles was a weak and

sickly infant. When Elizabeth I of England died in March 1603 and James VI

of Scotland became King of England as James I, Charles was not

considered strong enough to make the journey to London due to his fragile

health.[6] While his parents and older siblings

left for England in April and May that year, Charles remained in Scotland, with

his father's friend and the Lord President of the Court of Session, Alexander Seton, Lord Fyvie,

appointed as his guardian.[5]

By 1604, Charles was three

and a half and was by then able to walk the length of the great hall at

Dunfermline Palace unaided. It was decided that he was now strong enough to

make the journey to England to be reunited with his family and, on 13 July

1604, Charles left Dunfermline for England where he was to spend most of the

rest of his life.[7] In England, Charles was placed under

the charge of Alletta (Hogenhove) Carey, the Dutch-born wife of courtier Sir Robert Carey, who taught him how to talk

and insisted that he wear boots made of Spanish leather and brass to help

strengthen his weak ankles.[8] Charles apparently eventually

conquered his physical infirmity,[9] which might have been caused by rickets,[8] and grew to about a height of

5 feet 4 inches (163 centimetres).

[edit]Heir apparent

Charles as Duke of York and Albany, c. 1611

Charles was not as valued

as his physically stronger elder brother, Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales, whom

Charles adored and attempted to emulate.[10] In 1605, Charles was created Duke of York,

as is customary in the case of the sovereign's second son. However, when Henry

died of what is suspected to have been typhoid (or possibly porphyria)[11] at the age of 18 in 1612, two weeks

before Charles's 12th birthday, Charles became heir apparent.

As the eldest living son of the sovereign, Charles automatically gained several

titles (including Duke of Cornwall[12] and Duke of Rothesay).

Four years later, in November 1616, he was created Prince of Wales and Earl of Chester.[13]

Charles as Prince of Wales byIsaac Oliver,

1615

In 1613, his sister Elizabeth married Frederick V, Elector Palatine, and moved toHeidelberg.[14] In 1617, Ferdinand II, a Catholic, was elected

king of Bohemia. The following year, the people of Bohemia rebelled against their monarch, choosing to

crown Frederick V of the Palatinate, leader of the Protestant Union,

in his stead. Frederick's acceptance of the crown in September 1619 marked the

beginning of the turmoil that would develop into the Thirty Years' War. This conflict made a

great impression upon the English Parliament and public, who quickly grew to

see it as a polarised continental struggle between Catholics and Protestants.[15] James, who was supportive of his

son-in-law Frederick and had been seeking marriage between the new Prince of

Wales and the Spanish Infanta, Maria Anna of Spain, since Prince Henry's

death,[14] began to see theSpanish Match as a possible means of achieving peace

in Europe.[16]

Unfortunately for James, this

diplomatic negotiation with Spain proved generally unpopular, both with the

public and with James's court.[17] Arminian divines were the only source of

support for the proposed union.[18] Parliament was actively hostile

towards the Spanish throne,

and thus, when called by James, hoped for a crusade under the leadership of the

king[19] to rescue Protestants on the continent

from Habsburg rule.[20] Parliament's attacks upon the

monopolists for their abuse of prices led to the scapegoating of Francis Bacon by George Villiers, 1st Duke of

Buckingham,[21] and then to Bacon's impeachment before

the Lords. The impeachment was the first since 1459 without the King's official

sanction in the form of a bill of

attainder. The incident set an important precedent as to the

apparent scope of Parliament's authority to safeguard the nation's interests

and its capacity to launch legal campaigns, as it later did against Buckingham,

Archbishop Laud, the Earl of Strafford and Charles I. However, Parliament

and James came to blows when the issue of foreign policy was discussed. James

insisted that the Commons be concerned exclusively with domestic affairs, while

the members of the Commons protested that they had the privilege of free speech

within the Commons' walls.[22] Charles appeared to support his

brother-in-law's cause, but, like his father, he considered the discussion of

his marriage in the Commons impertinent and an infringement of his father's royal

prerogative.[23] In January 1622, James dissolved the

Parliament.[24]

[edit]Quarrel with Spain

Charles and the Duke of

Buckingham, James's favourite[25] and a man who had great influence over

the prince, travelled incognito together to Spain in 1623 to try to reach

agreement on the long-pending Spanish Match.[26] in the end, however, the trip was an

embarrassing failure. The Spanish demanded as a condition of the match that

Charles convert to Roman Catholicism and remain in Spain for a year after the

wedding as a hostage to ensure England's compliance with all the terms of the

treaty. Moreover, a personal quarrel erupted between Buckingham and the Spanish

nation between whom was mutual misunderstanding and ill temper.[27] Charles was outraged, and upon their

return in October, he and Buckingham demanded that King James declare war on

Spain.[26]

With the encouragement of

his Protestant advisers, James summoned Parliament in 1624 so that he could

request subsidies for a war.[28] At the behest of Charles and

Buckingham, James assented to the impeachment of the Lord Treasurer, Lionel Cranfield, 1st Earl of

Middlesex, by the House of Commons, who quickly fell in much the same

manner as Bacon had.[28]

James also requested that

Parliament sanction the marriage between the Prince of Wales and Princess Henrietta Maria of France,[29] whom Charles had met in Paris while en route to Spain.[30] It was a good match since she was a

sister of Louis XIII[31] (their father, Henry IV, had died during her

childhood). Parliament reluctantly agreed to the marriage,[31] with the promise from both James and

Charles that the marriage would not entail liberty of religion being accorded

to any Roman Catholic outside the Princess's own household.[31] By 1624, James was growing ill, and as

a result was finding it extremely difficult to control Parliament. By the time

of his death, March 1625, Charles and the Duke of Buckingham had already

assumed de facto control of the kingdom.[32]

|

Charles I |

Both Charles and James were

advocates of the divine right of kings, but whilst James's

lofty ambitions concerning absolute prerogative[33] were tempered by compromise and

consensus with his subjects, Charles I believed that he had no need of

Parliamentary approval, that his foreign ambitions (which were greatly

expensive and fluctuated wildly) should have no legal impediment, and that he

was himself above reproach. Charles believed that he had no need to compromise

or even to explain his actions, and that he was answerable only to God. He

famously said, "Kings are not bound to give an account of their actions

but to God alone".[34][35]

[edit]Early reign

On 11 May 1625 Charles was married by proxy to Henrietta Maria in front of the doors of the Notre Dame de Paris,[36]before

his first Parliament could meet to forbid the banns.[36] Many members were opposed to the

king's marrying a Roman Catholic, fearing that Charles would lift restrictions

on Roman Catholics and undermine the official establishment of the reformed Church of

England. Although he stated to Parliament that he would not relax

restrictions relating to recusants, he promised to

do exactly that in a secret marriage treaty with Louis XIII of France.[37] Moreover, the price of marriage with

the French princess was a promise of English aid for the French crown in the

suppressing of the Protestant Huguenots at La Rochelle,

thereby reversing England's long held position in the French Wars of Religion. The couple were

married in person on 13 June 1625 in Canterbury.

Charles was crowned on 2 February 1626 at Westminster

Abbey, but without his wife at his side due to the controversy.

Charles and Henrietta had seven children, with three sons and three daughters

surviving infancy.[38]

Sir Anthony Van Dyck: Charles I painted in April 1634. Despite

his reputation as a patron of the arts, Charles paid Van Dyck only half the

amount he requested

Distrust of Charles's

religious policies increased with his support of a controversial ecclesiastic, Richard Montagu.

In his pamphlets A New Gag for

an Old Goose, a reply to the Catholic pamphlet A New Gag for the new Gospel,

and also his Immediate

Addresse unto God alone, Montagu argued against Calvinist predestination,

thereby bringing himself into disrepute amongst the Puritans.[39] After a Puritan member of the House of

Commons, John Pym, attacked

Montagu's pamphlet during debate, Montagu requested the king's aid in another

pamphlet entitled Appello Caesarem (1625),

a reference to an appeal against Jewish persecution made by Saint Paul the

Apostle.[b] Charles made the cleric one of his

royal chaplains, increasing many Puritans' suspicions as to where Charles would

lead the Church, fearing that his favouring of Arminianism was a clandestine attempt on Charles's

part to aid the resurgence of Catholicism within the English Church.[40]

Charles's primary concern

during his early reign was foreign policy. The Thirty Years' War, originally confined to

Bohemia, was spiralling into a wider European war. In 1620 Frederick V was defeated at the Battle of White Mountain[41] and by 1622, despite the aid of

English volunteers, had lost his hereditary lands in the Electorate of the Palatinate to the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand II.[42] Having agreed to help his

brother-in-law regain the Palatinate, Charles declared war on Spain, which

under the Catholic King Philip IV had sent forces to help occupy the

Palatinate.[43]

Parliament preferred an

inexpensive naval attack on Spanish colonies in the New World, hoping that the

capture of the Spanish treasure fleets could finance the war. Charles, however,

preferred more aggressive (and more expensive) action on the Continent.[44] Parliament voted to grant a subsidy of

only £140,000, an insufficient sum for Charles.[45] Moreover, the House of Commons limited

its authorisation for royal collection of tonnage and poundage (two varieties of customs duties) to a

period of one year, although previous sovereigns since 1414 had been granted

the right for life.[45] In this manner, Parliament could keep

a check on expenditures by forcing Charles to seek the renewal of the grant

each year. Charles's allies in the House of Lords, led by the Duke of

Buckingham, refused to pass the bill. Although no Parliamentary Act for the

levy of tonnage and poundage was obtained, Charles continued to collect the

duties.[46]

The war with Spain under the leadership of Buckingham went badly, and the House of Commons

began proceedings for the impeachment of the duke.[47]Charles

nominated Buckingham as Chancellor of Cambridge University in response[48] and on 12 June 1626, the House of

Commons launched a direct protestation, stating, 'We protest before your

Majesty and the whole world that until this great person be removed from

intermeddling with the great affairs of state, we are out of hope of any good

success; and we do fear that any money we shall or can give will, through his

misemployment, be turned rather to the hurt and prejudice of your kingdom.'[48] Despite Parliament's protests,

however, Charles refused to dismiss his friend, dismissing Parliament instead.

Charles provoked further

unrest by trying to raise money for the war through a "forced loan":

a tax levied without Parliamentary consent. In November 1627, the test case in

the King's bench, the 'Five Knights' Case' –

which hinged on the king's prerogative right to imprison without trial those

who refused to pay the forced loan – was upheld on a general basis.[49] Summoned again in 1628, Parliament

adopted a Petition of

Right on 26 May,

calling upon the king to acknowledge that he could not levy taxes without

Parliament's consent, impose martial law on civilians, imprison them without

due process, or quarter troops in their homes.[50] Charles assented to the petition,[51] though he continued to claim the right

to collect customs duties without authorisation from Parliament.

Despite Charles's agreement

to suppress La Rochelle as a condition of marrying Henrietta Maria, Charles

reneged upon his earlier promise and instead launched a poorly conceived and

executed defence of the fortress under the leadership of Buckingham in

1628,[52] thereby driving a wedge between the

English and French Crowns that was not surmounted for the duration of the Thirty Years' War.[53] Buckingham's failure to protect the

Huguenots – indeed, his attempt to capture Saint-Martin-de-Ré then

spurred Louis XIII's attack on the Huguenot fortress of La Rochelle[54] – furthered Parliament's detestation

of the Duke and the king's close proximity to this eminence grise.

On 23 August 1628,

Buckingham was assassinated.[55] The public rejoicing at his death