Biscione

From

Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

![]() LES WINNILES VENAIENT DE SCANDINAVIE ET AVAIENT ADOPTE LE SERPENT

POUR LEUR ROI.

LES WINNILES VENAIENT DE SCANDINAVIE ET AVAIENT ADOPTE LE SERPENT

POUR LEUR ROI.

MAIS LA REINE SCYTHE TABITA ET DES PHARAONS TELS THOUTMOSIS III ET IV

L 'AVAIENT DEJA ADOPTE COMME LEUR

EMBLEME.

KROK LE FONDATEUR DE CRAKOVIE PERE DE LA REINE DE POLOGNE WANDA ET SELON LA LEGENDE LE VAINQUEUR DU DRAGON SERAIT UN ANCETRE DU

DUC QUI AURAIT ETE LE PREMIER WĄŻ

ET S 'EST VU ATTRIBUER

WężYKOWA WOLA PAR LE DUC SIEMOMYŚL PERE DE MIESZKO

PREMIER ROI CHRETIEN DE POLOGNE.LES WINNILES SE SONT MELANGES AVEC LES

VANDALES.LES WINNILES ONT CONQUIS L' ITALIE ET LES VANDALES ONT CONQUIS L

'ANDALOUSIE.DES AVIS LAISSENT PENSER QUE EN FAIT , il se pourrait que les

Goths, qui ont vécu en Pologne, soient des descendants des Scythes qui avaient

conquis l'Egypte, puisqu'on retrouve des vestiges de mêmes habitudes.

The biscione as a symbol of Milan,

seen here at the Central Station.

The Biscione (Italian

pronunciation: [biʃˈʃone]; Italian for ‘large grass snake’), also known as the Vipera (‘viper’ or in Milanese as

theBissa), is a heraldic charge showing

in Argent an Azure serpent

in the act of consuming a human; usually a child and sometimes described as a Moor.

It has been the emblem of the Italian Visconti family

for around a thousand years. Its iconographic origins date back to paleochristian times, to the biblical story of Jonah and the Leviathan in

the act of swallowing (and/or regurgitating) him, a common motif representing

the resurrection. How that widely known image can

be traced to the Visconti house is unknown; however, it has been claimed that

it was taken from the coat of arms of a Saracen killed

by Ottone Visconti during theCrusades")[citation needed].

Additionally, a man being swallowed by a serpent but being rescued features in

a number of legends

about Theoderic the Great, most prominently in the poem Virginal, where the city of Arona, which was owned by the Visconti, is

featured.

The figure may also represent the circumpolar

constellation Draco,

from whose "mouth" emerges the brilliant star Vega,

in constellation Lyra (symbolized as a falling vulture in Arabian astronomy;

Lyra is near Cygnus, which is the "Chicken" in Arabian astronomy;

Jonah may be related to both, because it means "Dove"),[citation needed] or also a symbol of the

"coiling" path of the Moon towards the eclipse points.

The biscione appears also in the coats of

arms of the House of Sforza,

the city of Milan,

the historical Duchy of Milan and Insubria, as well as the towns of Pruzhany (Belarus)

and Sanok (Poland); the presence of Biscione in Poland and Belarus is due to queen Bona Sforza. It is also used as a

symbol or logo by the football club Internazionale,

by espresso machine manufacturer Bezzera, by Alfa Romeo and,

in a version where a flower replaces the child, by Fininvest.

The biscione appears on the cover of an

American paperback edition of the Thomas Harris novel Hannibal.

The biscione also appears on the right side

of the logo for automaker Alfa Romeo.

Another version of the Biscione appears in

the seals of the Hungarian nobleman Nicholas I Garay, palatine to the King of Hungary (1375–1385).

The crowned snake instead of a man, it devoures a Sovereign's Orb.[1]

Wōden

From

Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Wodan Heals Balder's Horse by Emil Doepler (1855-1922).

This

article is about the Germanic god. For other uses, see Woden

(disambiguation) and Wotan

(disambiguation).

Woden or Wodan (Old English: Ƿōden,[1] Old High German: Wôdan,[2]Old Saxon: Uuôden[3]) is a major deity of Anglo-Saxon and Continental

Germanic polytheism. Together with his Norse counterpart[4] Odin,

Woden represents a development of the Proto-Germanic god *Wōdanaz.

Though less is known about the pre-Christian religion of Anglo-Saxon and

continental Germanic peoples than is known about Norse paganism, Woden is

attested in English, German, and Dutch toponyms as

well as in various texts and pieces of archeological evidence from the Early Middle Ages.

Contents

[hide] ·

3 Woden in Anglo-Saxon England ·

4 Medieval and Early Modern folklore ·

5 Legacy |

[edit]Etymology and origins

Main

article: Wōdanaz

*Wōđanaz or *Wōđinaz is the reconstructed Proto-Germanic name of a god of Germanic paganism. The name is connected to

the Proto-Indo-European stem *wāt,[5] "inspiration",[6] derived

ultimately from the Indo-European theme *awē,

"to blow". *Wāt continues in Old Irishfáith, "poet" or

"seer"; Old High German wut, "fury"; and Gothic wods,

"possessed".[7] Old

English had the noun wōþ "song,

sound", corresponding to Old Norse óðr, which has the meaning

"fury" but also "poetry, inspiration".[8] It

is possible therefore that *Wōđanaz was seen as a manifestation of

ecstasy, associated with mantic states,

fury, and poetic inspiration.[9] An

explicit association of Wodan with the state of fury was made by 11th century

German chronicler Adam of Bremen, who, when detailing the religious

practices ofScandinavian pagans, described Wodan, id est furor,

"Wodan, that is, the furious".[10]

Woden probably rose to prominence during the Migration period, gradually displacing Tyr as the head of the pantheon in

West and NorthGermanic cultures -- though such theories are only

academic speculation based on trends of worship for other Indo-European cognate

deity figures related to Tyr.

He is in all likelihood identical with the

Germanic god identified as "Mercury"

by Roman writers[11] and

possibly with the regnator omnium deus (god, ruler of all) mentioned by Tacitus in

his 1st century work Germania.[12]

The earliest attestation of the name is as Wodan (ᚹᛟᛞᚨᚾ) in an Elder Futhark

inscription: possibly on the Arguel pebble (of dubious authenticity, if genuine

dating to the early 6th century), and on the Nordendorf fibula (early 7th century). Only slightly

younger than the runic testimony of the Nordendorf fibula is the vita of Saint Columbanus by Jonas of Bobbio, which gives the Latinized Vodanus (attested in the dative, as Vodano). A further runic

inscription, on a brooch from Mülheim-Kärlich,

purportedly reading wodini

hailag "consecrated to Woden",

has long been recognized as a falsification.[13]

[edit]Continental Wodan

The

Nordendorf II fibula.

The

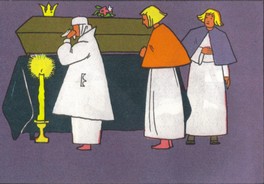

Winnili women wear their hair to look like long beards.

Details of Migration period Germanic religion are sketchy, reconstructed from

artifacts, sparse contemporary sources, and the later testimonies of medieval

legends and place names.

According to Jonas of Bobbio, the 6th century Irish

missionary Saint Columbanus is reputed to have interrupted an

offering being made by the Suebi to "their God Wodan".[14] "Wuodan"

was the chief god of the Alamanni, his name appears in the runic inscription

on the Nordendorf fibulae.

The Langobard historian Paul the Deacon, who died in southern Italy in

the 790s, was proud of his tribal origins and related how his people once had

migrated from southern Scandinavia.[15] In

his work Historia

Langobardorum, Paul states that "Wotan ... is adored as a

god by all the peoples of Germania"[16] and

relates how Godan's (Wotan's) wife Frea (Frijjo) had given victory to the Langobards in a war

against the Vandals.[15]The story is an etiology of the name

of the Lombards, interpreted as

"longbeards". According to the story, the Langobards were formerly

known as the "Winnili". In the war with the Vandals, Godan favoured

the Vandals, while Frea favoured the Winnili. After a heated discussion, Godan

swore that he would grant victory to the first tribe he saw the next morning upon

awakening—knowing full well that the bed was arranged so that the Vandals were

on his side. While he slept, Frea told the Winnili women to comb their hair

over their faces to look like long beards so they would look like men and

turned the bed so the Winnili women would be on Godan's side. When he woke up,

Godan was surprised to see the disguised women first and asked who these long

bearded men were, which was where the tribe got its new name, the

"longbeards".

Woden is mentioned in an Old Saxon baptismal vow

in Vatican Codex pal. 577 along with Thunear (Thor)

and Saxnōt. The 8th- or 9th-century vow,

intended for Christianising pagans, is recorded as:

ec forsacho allum dioboles

uuercum and uuordum, Thunaer ende Uuöden ende Saxnote ende allum them unholdum

the hira genötas sint

I forsake all devil's

work and words, Thunear and Wōden and Saxnōt and all them monsters

that are their retainers.[17]

Recorded during the 9th or 10th

century,[18] one

of the two Merseburg

Incantations, from Merseburg, Germany mentions

Wodan who rode into a wood together with Phol.

There Balder's horse was injured, and Wodan, together with goddesses, cured the

horse with enchantments (Phol is usually identified as Baldr).

[edit]Woden in

Anglo-Saxon England

"If a West Saxon

farmer in pagan times had walked out of his buryor ton above the Vale of Pewsey some autumn day, and looking up to the

hills had caught sight of a bearded stranger seeming in long cloak larger than

life as he stalked the skyline through the low cloud; and if they had met at

the gallows by the cross-roads where a body still dangled; and if the farmer

had noticed the old wanderer glancing up from under a shadowy hood or floppy

brimmed hat with a gleam of recognition out of his one piercing eye as though

acclaimed a more than ordinary interest, a positive interest, in the corpse;...

and if all this had induced in the beholder a feeling of awe; then he would

have been justified in believing that he was in the presence of Woden tramping

the world of men over his own Wansdyke."

Brian Branston, 1957.[19]

Anglo-Saxon

polytheism reached

Great Britain during the 5th and 6th centuries with the Anglo-Saxon migration,

and persisted until the completion of the Christianization

of England by the 8th

or 9th century.

For the Anglo-Saxons, Woden was the psychopomp or

carrier-off of the dead,[citation needed] but not necessarily with exactly the

same attributes of the Norse Odin. There has been some doubt as to whether the

early English had the concepts of Valkyries and Valhalla in

the Norse sense. The Sermo Lupi ad Anglos refers to the wælcyrian,

"valkyries", but the term appears to have itself been a loan from Old Norse, and in the text is used to mean

"(human) sorceress".[20]

The Christian writer of the Maxims found in the Exeter Book (341,

28) records the verse Wôden

worhte weos, wuldor alwealda rûme roderas("Woden wrought the (heathen)

altars / the almighty

Lord the wide

heavens"). The name of such Wôdenes

weohas (Saxon Wôdanes with, Norse Oðins ve) or sanctuaries to

Woden survives in toponymy as Odinsvi, Wodeneswegs.

[edit]Royal

genealogy

Main article: Anglo-Saxon

Genealogies

Further information: Kings of the Angles

Woden listed as an ancestor ofÆlfwald of East

Anglia in the Textus Roffensis (12th century).

As the Christianisation of England took

place, Woden was euhemerised as

an important historical king[21] and

was believed to be the progenitor of numerous Anglo-Saxon royal houses.[22]

Discussing the Anglo-Saxon

settlement of Britain, Bede,

in his Ecclesiastical

History of the English People (completed

in or before 731[23]) writes that:

The two first commanders are said to

have been Hengist and Horsa ... They were the sons of Victgilsus, whose father was Vecta,

son of Woden; from whose stock the royal race of many provinces deduce their

original.[24]

The Historia Brittonum,

composed around 830,[25] presents

a similar genealogy and additionally lists Woden as a descendent of Godwulf,[26] who

likewise in Snorri Sturluson's Prose Edda is said to be an ancestor of

"Vóden, whom we call Odin".[27][28]

According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle,

composed during the reign of Alfred the Great,[29] Woden

was the father of Wecta, Beldeg, Wihtgils and Wihtlaeg[30] and

was therefore an ancestor of theKings of Wessex, Northumbria, Mercia and East Anglia.

As in Bede's Ecclesiastical

History, a history of early Anglo-Saxon migration to Britain incorporating Woden

as an ancestor of Hengist and Horsa is given:

These men came from three tribes of

Germany: from the Old Saxons, from the Angles, and from the Jutes ... their

commanders were two brothers, Hengest and Horsa, that were the sons of

Wihtgils. Wihtgils was Witta's offspring, Witta Wecta's offspring, Wecta

Woden's offspring. From that Woden originated all our royal family ...[31]

Descent from Woden appears to have been

an important concept in Early Medieval England. According to N.J. Higham, claiming Woden as an ancestor had

by the 8th century become an essential way of establishing royal authority.[32] Richard

North (1997) believes similarly that "no king by the late seventh century

could do without the status that descent from Woden entailed."[33]

[edit]Nine Herbs

Charm

Recorded in the 10th century,[34] the Old English Nine Herbs Charm contains a mention of Woden:

A snake came crawling, it

bit a man.

Then Woden took nine

glory-twigs,

Smote the serpent so that

it flew into nine parts.

There apple brought this

pass against poison,

That she nevermore would

enter her house.[35]

According to R.K. Gordon, the Nine Herbs Charm is an originally pagan spell altered

by later Christian interpolation.[36] Baugh

andMalone (1959)

write that "This narrative ... is a precious relic of English heathendom;

unluckily we do not know the Woden myth which it summarizes."[37] A

charm from the same period, Wið færstice, refers to the esa[38] ("gods",[39] cognate

of Norse æsir) but does not mention any deities by

name.

[edit]Medieval and Early Modern folklore

Woden persisted as a figure in folklore

and folk religion throughout the Middle Ages and into the modern period,

notably as the leader of the Wild Hunt found

in English, German, Swiss, and Scandinavian traditions.[40]

Woden is thought to be the precursor of

the English Father Christmas, or Father Winter, and the American Santa Claus.[41][42][43][44][45][46][47]

A celebrated late attestation of invocation

of Wodan in Germany dates to 1593, in Mecklenburg, where the formula Wode, Hale dynem Rosse nun Voder "Wodan, fetch now food for your

horse" was spoken over the last sheaf of the harvest.[48] David

Franck adds, that at the squires' mansions, when the rye is all cut, there is Wodel-beer served out to the mowers; no one weeds

flax on a Wodenstag, lest Woden's horse should trample the seeds; from

Christmas to Twelfth-day they will not spin, nor leave any flax on the distaff,

and to the question why? they answer, Wode is galloping across. We are

expressly told, this wild hunter Wode rides a white horse. (34)

A custom in Schaumburg is

reported by Jacob Grimm: the people go out to mow in

parties of twelve, sixteen or twenty scythes, but it is managed in such a

manner, that on the last day of harvest they are all finished at the same time,

or some leave a strip standing which they can cut down at a stroke the last

thing, or they merely pass their scythes over the stubble, pretending there is

still some left to mow. At the last stroke of the scythe they raise their

implements aloft, plant them upright, and beat the blades three times with the

strop. Each spills on the field a little of the drink he has, whether beer,

brandy, or milk, then drinks himself, while they wave their hats, beat their

scythes three times, and cry aloud Wôld,

Wôld, Wôld! and the women

knock all the crumbs out of their baskets on the stubble. They march home

shouting and singing. If the ceremony was omitted, the following year would

bring bad crops of hay and corn. The first verse of the song is quoted by

Grimm,

|

„Wôld, Wôld, Wôld! |

“Wôld, Wôld, Wôld”! |

Grimm notes that the custom had died

out in the fifty years preceding his time of writing (1835)[citation needed].

In England there are also folkloric

references to Woden, including the "giants' dance" of Woden and Frigg

in Dent as recorded by Grimm,[49] and

the Lincolnshire charm that contained the line "One for God, one for Wod

and one for Lok".[50] Other

references include the Northumbrian Auld

Carl Hood from the ballad Earl Brand,[51] Herla,[52][53][54][55] Woden's

role as the leader of the Wild Hunt inNorthern England[56][57][58][59] and

quite possibly Herne, the Wild Huntsman of Berkshire.[60][61][62][63]

[edit]Legacy

[edit]Toponyms

Main article: List of

places named after *Wodanaz

Grimm (Teutonic Mythology, ch. 7) discusses traces of Woden's name in toponymy. Certain mountains were sacred to the

service of the god. Othensberg,

now Onsberg,

on the Danish island of Samsø; Odensberg in Schonen. Godesberg near Bonn,

from earlierWôdenesberg (annis

947, 974). Near the holy oak in Hesse, which Boniface brought down, there stood

a Wuodenesberg, still so

named in a document of 1154, later Vdenesberg,

Gudensberg; this hill is not to be confounded with Gudensberg by Erkshausen,

nor with a Gudenberg by Oberelsungen and Zierenberg so that three mountains

of this name occur in Lower Hesse alone;

conf. montem Vodinberg, cum

silva eidem monti attinente, (doc.

of 1265). In a different neighbourhood, a Henricus

comes de Wôdenesberg is named

in a doc. of 1130. A Wôdnes

beorg in the Saxon Chronicle,

later Wodnesborough, Wanborough in Wiltshire. A Wôdnesbeorg in Lappenberg's map near the Bearucwudu, conf. Wodnesbury, Wodnesdyke, Wôdanesfeld.

To this we must add, that about the Hessian Gudensberg the story goes that King Charles lies

prisoned in it, that he there won a victory over the Saxons, and opened a well

in the wood for his thirsting army, but he will yet come forth of the mountain,

he and his host, at the appointed time. The mythus of a victorious army pining

for water is already applied to King Carl by the Frankish annalists, at the

very moment when they bring out the destruction of the Irminsul; but beyond a doubt it is

older : Saxo Grammaticus has it of the victorious Balder.

The breviarium

Lulli, in names a place in Thuringia: in

Wudaneshusum, and again Woteneshusun; in Oldenburg there

is a Wodensholt, now Godensholt,

cited in a land-book of 1428; Wothenower,

seat of a Brandenburg family anno 1334; not far from Bergen op Zoom, towards Antwerp, stands to

this day a Woensdrecht, as if Wodani trajectum. Woensel = Wodenssele, Wodani aula, a so-calledstadsdeel of

the city of Eindhoven on

the Dommel in Northern Brabant. This Woensel is like the Oðinssalr, Othänsäle, Onsala; Wunstorp, Wunsdorf, a convent

and small town in Lower Saxony, stands unmutilated as Wodenstorp in a document of 1179. Near Windbergen in

the Ditmar country, an open space in a wood bears the name of Wodenslag, Wonslag. Near Hadersleben in

Schleswig are the villages ofWonsbeke, Wonslei, Woyens formerly Wodensyen. An Anglo-Saxon

document of 862 contains in a boundary-settlement the nameWônstoc = Wôdenesstoc, Wodani stipes, and at the same

time betrays the influence of the god on ancient delimitation (Wuotan, Hermes,

Mercury, all seem to be divinities of measurement and demarcation)

Wensley,[64][65][66] Wednesbury,[67][68] Wansdyke[69][70] and Wednesfield[68] are

named after Woden. Also, the Woden Valley inCanberra, Australia is

named after Woden.

[edit]Wednesday

Wednesday (Wēdnes

dæg, "Woden's day", interestingly continuing the variant *Wōdinaz (with umlaut of ō to ē),

unlike Wōden,

continuing *Wōdanaz) is named after him, his link with the dead

making him the appropriate match to the Roman Mercury.

[edit]See also

· Continental

Germanic mythology

· List of

places named after Woden

· Mythology of

the Low Countries

· Urglaawe

· Weoh

Wansdyke

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Wansdyke may

refer to:

·

Wansdyke

(UK Parliament constituency)

Lombards

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

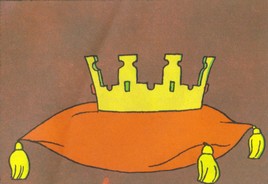

The Iron Crown of

Lombardy, used for the coronation of thekings of Italy until 1946

The Lombards or Langobards (Latin: Langobardī),

were a Germanic tribewho ruled a Kingdom in Italy from 568 to 774.

The Lombard historian Paul the Deacon wrote in the Historia

Langobardorumthat the Lombards descended from a small tribe

called the Winnili[1] who

dwelt in southern Scandinavia[2] (Scadanan)

before migrating to seek new lands. In the 1st century AD they formed part of

the Suebi,

in northwesternGermany. By the end of the 5th century they

had moved into the area roughly coinciding with modern Austria north

of the Danube river,

where they subdued the Heruls and

later fought frequent wars with the Gepids.

The Lombard kingAudoin defeated

the Gepid leader Thurisind in

551 or 552; his successorAlboin eventually destroyed the Gepids at the Battle of Asfeld in 567.

Following this victory, Alboin decided to

lead his people to Italy, which had become severely depopulated after the long Gothic War (535–554) between the Byzantine Empire and the Ostrogothic Kingdom there. The Lombards were joined by

numerous Saxons, Heruls, Gepids, Bulgars, Thuringians, and Ostrogoths, and their invasion of Italy was

almost unopposed. By late 569 they had conquered all the principal cities north

of the Po River except Pavia,

which fell in 572. At the same time, they occupied areas in central and southern Italy. They established a Lombard

Kingdom in Italy, later named Regnum Italicum ("Kingdom of Italy"), which

reached its zenith under the 8th-century ruler Liutprand.

In 774, the Kingdom was conquered by the Frankish KingCharlemagne and

integrated into his Empire. However, Lombard nobles continued to

rule parts of the Italian peninsula well into the 11th century when they

were conquered by the Normans and

added to their County of Sicily. Their legacy is apparent in

the regional appellation, Lombardy.

[edit]History

[edit]Early history

Paul the Deacon, historian of the Lombards,

circa 720-799.

[edit]Legendary origins and name

Further

information: Hundings

The fullest account of Lombard origins,

history, and practices is the Historia

Langobardorum(History of the Lombards) of Paul the Deacon, written in the 8th century.

Paul's chief source for Lombard origins, however, is the 7th-century Origo Gentis Langobardorum (Origin of the Lombard People).

The Origo

Gentis Langobardorum tells

the story of a small tribe called the Winnili[1] dwelling

in southern Scandinavia[2] (Scadanan)

(the Codex Gothanus writes that the Winnili first dwelt

near a river called Vindilicus on the extreme boundary of Gaul).[3] The

Winnili were split into three groups and one part left their native land to

seek foreign fields. The reason for the exodus was probably overpopulation.[4] The

departing people were led by the brothers Ybor and Aio and their mother Gambara[5] and

arrived in the lands of Scoringa,

perhaps the Baltic coast[6] or

the Bardengau on

the banks of the Elbe.[7] Scoringa

was ruled by the Vandals and

their chieftains, the brothers Ambri and Assi, who granted the Winnili a choice

between tribute or war.

The Winnili were young and brave and refused

to pay tribute, saying "It is better to maintain liberty by arms than to

stain it by the payment of tribute."[8] The

Vandals prepared for war and consulted Godan (the god Odin[2]), who answered that he would give

the victory to those whom he would see first at sunrise.[9] The

Winnili were fewer in number[8] and

Gambara sought help from Frea (the goddess Frigg[2]), who advised that all Winnili women

should tie their hair in front of their faces like beards and march in line

with their husbands. So Godan spotted the Winnili first and asked, "Who

are these long-beards?," and Frea replied, "My lord, thou hast given

them the name, now give them also the victory."[10] From

that moment onwards, the Winnili were known as the Longbeards (Latinised as Langobardi, Italianised as Lombardi, and Anglicized as Lombards).

When Paul the Deacon wrote the Historia between 787 and 796 he was a Catholic monk

and devoted Christian. He thought the paganstories of his people "silly"

and "laughable".[9][11] Paul

explained that the name "Langobard" came from the length of their

beards.[12] A

modern theory suggests that the name "Langobard" comes from Langbarðr, a name of Odin.[13] Priester

states that when the Winnili changed their name to "Lombards", they

also changed their old agricultural fertility cult to a cult of Odin, thus creating a

conscious tribal tradition.[14] Fröhlich

inverts the order of events in Priester and states that with the Odin cult, the

Lombards grew their beards in resemblance of the Odin of tradition and their

new name reflected this.[15] Bruckner

remarks that the name of the Lombards stands in close relation to the worship

of Odin, whose many names include "the Long-bearded"

or "the Grey-bearded", and that the Lombard given name Ansegranus ("he with the beard of the

gods") shows that the Lombards had this idea of their chief deity.[16]

[edit]Archaeology and migrations

From the combined testimony of Strabo (AD

20) and Tacitus (AD

117), the Lombards dwelt near the mouth of the Elbe shortly after the beginning of the Christian

era, next to the Chauci.[17] Strabo

states that the Lombards dwelt on both sides of the Elbe.[18] The

German archaeologist Willi Wegewitz defined several Iron Age burial

sites at the lower Elbe as Langobardic.[19] The

burial sites are crematorial and are usually dated from the 6th century BC

through the 3rd AD, so a settlement breakoff seems unlikely.[20] The

lands of the lower Elbe fall into the zone of the Jastorf Culture and became Elbe-Germanic, differing from the lands

between Rhine, Weser,

and the North Sea.[21] Archaeological

finds show that the Lombards were an agricultural people.[22]

Distribution

of Langobardic burial fields at the Lower Elbe Lands, according to W. Wegewitz

The first mention of the Lombards occurred

between AD 9 and 16, by the Romancourt historian Velleius Paterculus,

who accompanied a Roman expedition as prefect of the cavalry.[17] Paterculus

described the Lombards as "more fierce than ordinary German

savagery."[23] Tacitus counted

the Lombards as a Suebiantribe,[24] and

subjects of Marobod the

King of the Marcomanni.[25] Marobod

had made peace with the Romans, and that is why the Lombards were not part of

the Germanic confederacy under Arminius at

the Battle of

Teutoburg Forest in AD

9. In AD 17, war broke out between Arminius and Marobod. Tacitus records:

Not only the Cheruscans and their

confederates... took arms, but the Semnones and Langobards, both Suevian

nations, revolted to him from the sovereignty of Marobod... The armies... were

stimulated by reasons of their own, the Cheruscans and the Langobards fought

for their ancient honor or their newly acquired independence. . . "[24]

In 47, a struggle ensued amongst the Cherusci and

they expelled their new leader, the nephew of Arminius, from their country. The

Lombards appeared on the scene with sufficient power to control the destiny of

the tribe that had been the leader in the struggle for independence thirty-eight

years earlier, for they restored the deposed leader to sovereignty again.[26] In

the mid-2nd century, the Lombards appeared in the Rhineland. According to Ptolemy, the Suebic Lombards settled south of

the Sugambri[27] but

also remained on the Elbe, between the Chauci and the Suebi,[28] indicating

a Lombard expansion. The Codex

Gothanus also mentions Patespruna (Paderborn) in connection with the Lombards.[29] Cassius Dio reported

that just before the Marcomannic Wars, 6,000 Lombards and Ubii crossed the Danube and

invaded Pannonia.[30] The

two tribes were defeated, whereupon they desisted from their invasion and sent

Ballomar, King of the Marcomanni, as ambassador to Aelius

Bassus, who was then administering Pannonia. Peace was made and the

two tribes returned to their homes, which in the case of the Lombards was the

lands of the lower Elbe.[31] At

about this time, Tacitus, in his work Germania (AD 98), describes the Lombards as

such:

To the Langobardi, on the contrary, their

scanty numbers are a distinction. Though surrounded by a host of most powerful

tribes, they are safe, not by submitting, but by daring the perils of war.

From the 2nd century onwards, many of the

Germanic tribes recorded as active during the Principate started to unite into

bigger tribal unions, resulting in the Franks, Alamanni, Bavarii, and Saxons.[32] The

Lombards may disappear from Roman history from 166–489 because they dwelt so

deep within Inner Germania that they were detectable only when they reappeared

on the banks of the Danube, or because they were subjected to a larger tribal

union, like the Saxons.[32] It

is, however, highly probable that when the bulk of the Lombards migrated, a

considerable part remained behind and afterwards became absorbed by the Saxon

tribes in the region, while the emigrants alone retained the name of Lombards.[33] However,

the Codex Gothanus states that the Lombards were

subjected by the Saxons around 300 but rose up against them under their first

king, Agelmund, who ruled for thirty years.[34] In

the second half of the 4th century, the Lombards left their homes, probably due

to bad harvests, and embarked on their migration.[35]

Lombard

migration from Scandinavia

The migration route of the Lombards in 489,

from their homeland to "Rugiland", encompassed several places: Scoringa (believed to be the their land on the

Elbe shores), Mauringa, Golanda,Anthaib, Banthaib, and Vurgundaib (Burgundaib).[36] According

to the Ravenna Cosmography,

Mauringa was the land east of the Elbe.[37]

The crossing into Mauringa was very

difficult. The Assipitti (Usipetes) denied them passage through their lands and

a fight was arranged for the strongest man of each tribe. The Lombard was

victorious, passage was granted, and the Lombards reached Mauringa.[38]

The Lombards departed from Mauringa and

reached Golanda. Scholar Ludwig Schmidt thinks this was further east, perhaps

on the right bank of the Oder.[39] Schmidt

considers the name the equivalent of Gotland, meaning simply "good land."[40] This

theory is highly plausible; Paul the Deacon mentions the Lombards crossing a

river, and they could have reached Rugiland from the Upper Oder area via the Moravian Gate.[41]

Moving out of Golanda, the Lombards passed

through Anthaib and Banthaib until they reached Vurgundaib, believed to be the

old lands of the Burgundes.[42][43] In

Vurgundaib, the Lombards were stormed in camp by "Bulgars" (probably Huns)[44] and

were defeated; King Agelmund was killed and Laimicho was made king. He was in his

youth and desired to avenge the slaughter of Agelmund.[45] The

Lombards themselves were probably made subjects of the Huns after the defeat

but rose up and defeated them with great slaughter,[46] gaining

great booty and confidence as they "became bolder in undertaking the toils

of war."[47]

In the 540s, Audoin (ruled

546–560) led the Lombards across the Danube once more into Pannonia, where they received Imperial

subsidies as Justinian encouraged

them to battle the Gepids.

[edit]Kingdom in Italy

Main

article: Kingdom of the

Lombards

[edit]Invasion and conquest of the Italian

peninsula

The

Lombard possessions in Italy: The Lombard Kingdom (Neustria, Austria and Tuscia) and the Lombard Duchies of Spoleto and

Benevento

In 560, Audoin was succeeded by his son Alboin, a young and energetic leader who defeated the

neighboring Gepidae and

made them his subjects; in 566, he marriedRosamund,

daughter of the Gepid king Cunimund. In the spring of 568, Alboin led the

Lombard migration into Italy:[48]

"Then the Langobards, having left Pannonia, hastened to take possession of Italywith

their wives and children and all their goods." B.2-Ch.7

Various other people who either voluntarily

joined or were subjects of King Alboin were

also part of the migration:[48]

"Whence, even until today, we call

the villages in which they dwell Gepidan,Bulgarian, Sarmatian, Pannonian, Suabian, Norican, or by other names of this kind."

B.2-Ch.26

The first important city to fall was Forum Iulii (Cividale del Friuli)

in northeastern Italy, in 569. There, Alboin

created the first Lombard duchy, which he entrusted to his nephewGisulf. Soon Vicenza, Verona and Brescia fell

into Germanic hands. In the summer of 569, the Lombards conquered the main

Roman centre of northern Italy, Milan.

The area was then recovering from the terrible Gothic Wars,

and the small Byzantine army

left for its defence could do almost nothing. The Exarch sent

to Italy by Emperor Justin II, Longinus, could defend only coastal

cities that could be supplied by the powerful Byzantine fleet. Pavia fell after a siege of three years, in

572, becoming the first capital city of the new Lombard kingdom of Italy. In

the following years, the Lombards penetrated further south, conquering Tuscany and

establishing two duchies, Spoleto and Benevento under Zotto,

which soon became semi-independent and even outlasted the northern kingdom,

surviving well into the 12th century. The Byzantines managed

to retain control of the area of Ravenna and Rome, linked by a thin corridor

running through Perugia.

When they entered Italy, some Lombards

retained their native form of paganism, while some were Arian Christians.

Hence they did not enjoy good relations with the Catholic Church. Gradually, they adopted Roman

titles, names, and traditions, and partially converted to orthodoxy (in the 7th

century), though not without a long series of religious and ethnic conflicts.

By the time Paul the Deacon was writing, the Lombard language,

dress and even hairstyles had all disappeared.[49]

The whole Lombard territory was divided into

36 duchies, whose leaders settled in the main cities. The king ruled over them

and administered the land through emissaries called gastaldi. This subdivision,

however, together with the independent indocility of the duchies, deprived the

kingdom of unity, making it weak even when compared to the Byzantines,

especially after they began to recover from the initial invasion. This weakness

became even more evident when the Lombards had to face the increasing power of

the Franks. In response, the kings tried to centralize power over time, but

they definitively lost control over Spoleto and Benevento in

the attempt.

[edit]Langobardia major

[edit]Langobardia minor

·

Duchy of Spoleto and List of Dukes of

Spoleto

·

Duchy of Benevento and List

of Dukes and Princes of Benevento

[edit]Arian monarchy

The

Frankish Merovingian King Chlothar IIin combat with the Lombards

In 572 Alboin was murdered in Verona in a

plot led by his wife, Rosamund, who later fled toRavenna. His successor, Cleph,

was also assassinated, after a ruthless reign of 18 months. His death began an

interregnum of years (the "Rule of the Dukes") during which the dukes did

not elect any king, a period regarded as a time of violence and disorder. In

584, threatened by a Frankish invasion, the dukes elected as king Cleph's son, Authari. In 589, he marriedTheodelinda, daughter of Garibald I of Bavaria,

the Duke of Bavaria. The Catholic Theodelinda was

a friend of Pope Gregory I and pushed for Christianization. In

the meantime, Authari embarked on a policy of internal reconciliation and tried

to reorganize royal administration. The dukes yielded half their estates for

the maintenance of the king and his court in Pavia. On the foreign affairs

side, Authari managed to thwart the dangerous alliance between the Byzantines

and the Franks.

Authari died in 591 and was succeeded by Agilulf, the duke of Turin,

who also married Theodelinda in the same year. Agilulf successfully fought the

rebel dukes of northern Italy, conquering Padua in 601, Cremona and Mantua in

603, and forcing the Exarch of Ravenna to pay tribute. Agilulf died in 616;

Theodelinda reigned alone until 628 when she was succeeded by Adaloald. Arioald, the head of the Arian opposition who

had married Theodelinda's daughter Gundeperga, later deposed Adaloald.

Arioald was succeeded by Rothari, regarded by many authorities as the

most energetic of all Lombard kings. He extended his dominions, conquering Liguria in

643 and the remaining part of the Byzantine territories of inner Veneto, including the Roman city of Opitergium(Oderzo). Rothari also made the famous edict bearing his

name, the Edictum Rothari, which established the

laws and the customs of his people in Latin:

the edict did not apply to the tributaries of the Lombards, who could retain

their own laws. Rothari's son Rodoaldsucceeded him in 652, still very young,

and was killed by the Catholic party.

At the death of King Haripert I in 661, the kingdom was split between

his children Perctarit, who set his capital in Milan, and Godepert, who reigned from Pavia.

Perctarit was overthrown by Grimoald,

son of Gisulf, duke of Friuli and

Benevento since 647. Perctarit fled to theAvars and

then to the Franks. Grimoald managed to regain control over the duchies and

deflected the late attempt of the Byzantine emperor Constans II to conquer southern Italy. He also

defeated the Franks. At Grimoald's death in 671 Perctarit returned

and promoted tolerance between Arians and Catholics, but he could not defeat

the Arian party, led by Arachi, duke of Trento, who submitted only to his son, the philo-Catholic Cunincpert.

The Lombards engaged in fierce battles with Slavic peoples during these years: In 623–26 the

Lombards unsuccessfully attackedCarantanians; in 663–64, the Slavs raided the Vipava Valley and the Friuli.

[edit]Catholic monarchy

King Liutprand - (712-744)

"was a zealous Catholic, generous and a great founder of

monasteries" [50]

Religious strife and the Slavic raids

remained a source of struggle in the following years. In 705, the Friuli

Lombards were defeated and lost the land to the west of the Soča River,

namely the Gorizia Hills and the Venetian Slovenia.[51] A

new ethnic border was established that has lasted for over 1200 years up until

the present time.[51][52]

The Lombard reign began to recover only with Liutprand the Lombard (king from 712), son ofAnsprand and

successor of the brutal Aripert II. He managed to regain a certain

control overSpoleto and

Benevento, and, taking advantage of the disagreements between the Pope and

Byzantium concerning the reverence of icons, he annexed the Exarchate

of Ravenna and the duchy of Rome.

He also helped the Frankish marshal Charles Martel to drive back theArabs.

The Slavs were defeated in the Battle

of Lavariano, when they tried to conquer theFriulian Plain in 720.[51] Liutprand's

successor Aistulf conquered

Ravenna for the Lombards for the first time, but was subsequently defeated by

the king of the Franks Pippin III, called by the Pope, and had to

leave it. After the death of Aistulf, Ratchis tried

once again to be king of the Lombardy but he was deposed in the same year.

After his defeat of Ratchis, the last Lombard

to rule as king was Desiderius, duke of Tuscany, who managed to take Ravenna

definitively, ending the Byzantine presence

in northern Italy. He decided to reopen struggles against the Pope, who was

supporting the dukes of Spoleto and Benevento against him, and entered Rome in

772, the first Lombard king to do so. But when Pope Hadrian I called for help from the powerful king Charlemagne, Desiderius was defeated at Susa and

besieged in Pavia,

while his son Adelchis had

also to open the gates of Verona to Frankish troops. Desiderius surrendered in

774 and Charlemagne, in an utterly novel decision, took the title "King of

the Lombards" as well. Before then the Germanic kingdoms had frequently

conquered each other, but none had adopted the title of King of another people.

Charlemagne took part of the Lombard territory to create the Papal States.

The Lombardy region

in Italy, which includes the cities of Brescia, Bergamo, Milan and the old

capital Pavia, is a reminder of the presence of the Lombards.

[edit]Later history

Lombard Duchy of Benevento in the 8th century AD

[edit]United Principality of Benevento

Though the kingdom centred on Pavia in the

north fell to Charlemagne, the Lombard-controlled territory to the south of the

Papal States was never subjugated by Charlemagne or his descendants. In 774,

Duke Arechis II of

Benevento, whose duchy had only nominally been under royal

authority, though certain kings had been effective at making their power known

in the south, claimed that Benevento was the successor state of the kingdom. He tried to turn

Benevento into a secundum

Ticinum: a second Pavia. He tried to claim the kingship, but with no

support and no chance of a coronation in Pavia.

Charlemagne came down with an army, and his

son Louis the Pious sent men, to force the Beneventan duke

to submit, but his submission and promises were never kept and Arechis and his

successors were de facto independent. The Beneventan dukes took

the title princeps (prince) instead of that of king.

The Lombards of southern Italy were

thereafter in the anomalous position of holding land claimed by two empires:

the Carolingian Empireto

the north and west and the Byzantine Empire to the east. They typically made

pledges and promises of tribute to the Carolingians, but effectively remained

outside Frankish control. Benevento meanwhile grew to its greatest extent yet

when it imposed a tribute on theDuchy of Naples, which was tenuously loyal to

Byzantium and even conquered the Neapolitan city of Amalfi in

838. At one point in the reign of Sicard,

Lombard control covered most of southern Italy save the very south of Apulia and Calabria and

Naples, with its nominally attached cities. It was during the 9th century that

a strong Lombard presence became entrenched in formerly Greek Apulia. However,

Sicard had opened up the south to the invasive actions of the Saracens in

his war with Andrew II of Naples and when he was assassinated in 839,

Amalfi declared independence and two factions fought for power in Benevento,

crippling the principality and making it susceptible to external enemies.

The civil war lasted ten years and was ended

only by a peace treaty imposed by the Emperor Louis II, the only Frankish king to

exercise actual sovereignty over the Lombard states, in 849, which divided the

kingdom into two states: the Principality of Benevento and thePrincipality of

Salerno, with its capital at Salerno on

the Tyrrhenian.

[edit]Southern

Italy and the Arabs, 836–915

Main

article: History

of Islam in southern Italy

Andrew II of Naples hired Saracen mercenaries

for his war with Sicard of Benevento in 836; Sicard responded with other Muslim

mercenaries. The Saracens initially concentrated their attacks on Sicily and

Byzantine Italy, but soon Radelchis I of

Benevento called in

more mercenaries who destroyed Capua in 841. Landulf the Old founded the present-day Capua,

"New Capua", on a nearby hill. In general, the Lombard princes were

less inclined to ally with the Saracens than with their Greek neighbours of

Amalfi, Gaeta, Naples and Sorrento. Guaifer of Salerno,

however, briefly put himself under Muslim suzerainty.

A large Muslim force seized Bari,

until then a Lombard gastaldate under the control of Pandenulf,

in 847. Saracen incursions proceeded northwards until Adelchis of Benevento called in the help of his suzerain,

Louis II. Louis allied with the Byzantine emperor Basil I to

expel the Arabs from Bari in 869. An Arab landing force was defeated by the

emperor in 871. Adelchis and Louis were at war for the rest of the latter's

career. Adelchis regarded himself as the true successor of the Lombard kings

and in that capacity he amended the Edictum Rothari, the last Lombard ruler to

do so.

After Louis's death, Landulf II of Capua briefly flirted with a Saracen

alliance, but Pope John VIII convinced him to break it off. Guaimar I of Salerno fought the Saracens with Byzantine

troops. Throughout this period the Lombard princes swung in allegiance from one

party to another. Finally, towards 915, Pope John X managed

to unite the Christian princes of southern Italy against the Saracen

establishments on the Garigliano river.

That year, in the Battle of the

Garigliano, the Saracens were ousted from Italy.

Italy

around the turn of the millennium, showing the Lombard states in the south on

the eve of the arrival of the Normans.

[edit]The Lombard principalities

in the 10th century

The independent state at Salerno inspired the gastalds of Capua to move towards independence and, by

the end of the century, they were styling themselves "princes" and

there was a third Lombard state. The Capuan and Beneventan states were united

byAtenulf I of Capua in 900. He subsequently declared them

to be in perpetual union and they were separated only in 982, on the death of Pandulf Ironhead. With all of the Lombard

south under his control save Salerno, Atenulf felt safe in using the title princeps gentis Langobardorum ("prince of the Lombard

people"), which Arechis II had begun using in 774. Among Atenulf's

successors the principality was ruled jointly by fathers, sons, brothers,

cousins, and uncles for the greater part of the century. Meanwhile, the princeGisulf I of Salerno began using the title Langobardorum gentis princeps around mid-century, but the ideal of a

united Lombard principality was realised only in December 977, when Gisulf died

and his domains were inherited by Pandulf Ironhead, who temporarily held almost

all Italy south of Rome and brought the Lombards into alliance with the Holy Roman Empire. His territories were

divided upon his death.

Landulf the Red of Benevento and Capua tried to

conquer the principality of Salerno with the help of John III of Naples,

but with the aid of Mastalus I of Amalfi Gisulf repulsed him. The rulers of

Benevento and Capua made several attempts on Byzantine Apulia at this time, but late in the century,

the Byzantines, under the stiff rule of Basil II, gained ground on the Lombards.

The principal source for the history of the

Lombard principalities in this period is theChronicon

Salernitanum, composed late in the 10th century at Salerno.

[edit]Norman

conquest, 1017–1078

Main

article: Norman

conquest of southern Italy

The diminished Beneventan principality soon

lost its independence to the papacy and

declined in importance until it fell in the Normanconquest

of southern Italy. The Normans, first called in by the Lombards to

fight the Byzantines for control of Apulia and Calabria (under

the likes of Melus of Bari and Arduin, among

others), had become rivals for hegemony in the south. The Salernitan principality

experienced a golden age under Guaimar III and Guaimar IV,

but under Gisulf II,

the principality shrank to insignificance and fell in 1078 toRobert Guiscard, who had married Gisulf's

sister Sichelgaita. The Capua principality was hotly

contested during the reign of the hatedPandulf IV,

the Wolf of the Abruzzi,

and, under his son, it fell, almost without contest, to the Norman Richard Drengot (1058). The Capuans revolted against

Norman rule in 1091, expelling Richard's grandson Richard II and setting up one Lando IV.

Capua was again put under Norman rule after

the Siege of Capua of 1098 and the city quickly declined

in importance under a series of ineffectual Norman rulers. The independent

status of these Lombard states is in general attested by the ability of their

rulers to switch suzerains at will. Often the legal vassal of pope or emperor

(either Byzantine or Holy Roman),

they were the real power-brokers in the south until their erstwhile allies, the

Normans, rose to preeminence: The Lombards regarded the Normans as barbarians

and the Byzantines as oppressors. Regarding their own civilisation as superior,

the Lombards did indeed provide the environment for the illustriousSchola Medica

Salernitana.

[edit]Culture

[edit]Language

Main

article: Lombardic language

The Lombardic language is extinct (unless Cimbrian and Mocheno represent

surviving dialects).[53] The Germanic language declined beginning in the 7th century,

but may have been in scattered use until as late as about the year 1000. The

language is preserved only fragmentarily, the main evidence being individual

words quoted in Latin texts. In the absence of Lombardic

texts, it is not possible to draw any conclusions about the language's morphology

and syntax. The genetic classification the language is based entirely on

phonology. Since there is evidence that Lombardic participated in, and indeed

shows some of the earliest evidence for, the High German

consonant shift, it is classified as an Elbe Germanic or Upper German dialect.

Lombardic fragments are preserved in runic inscriptions. Among the primary source

texts are short inscriptions in the Elder Futhark, among them the "bronze

capsule of Schretzheim" (c. 600). There are a number

of Latin texts that include Lombardic names, and Lombardic legal texts contain

terms taken from the legal vocabulary of the vernacular. In 2005, there were

claims that the inscription of thePernik sword may

be Lombardic.

The Italian language preserves a large number

of Lombardic words, although it is not always easy to tell them apart from

those stemming from other Germanic languages such as Gothic and Frankish. They

often bear some resemblance to English words as Lombardic was akin to Saxon.

For instance, landa from land, guardia from wardan (warden), guerra from werra (war), guadare from wadjan (to wade).

[edit]Social

structure

[edit]Migration Period society

The Lombard kings can be traced back as early

as c. 380 and thus to the beginning of the

Great Migration. Kingship developed amongst the Germanic peoples when the unity

of a single military command was found necessary. Schmidt believed that the

Germanic tribes were divided according to cantons and that the earliest government was a

general assembly that selected the chiefs of the cantons and the war leaders from

the cantons (in times of war). All such figures were probably selected from a

caste of nobility. As a result of wars of their wanderings, royal power

developed such that the king became the representative of the people; but the

influence of the people upon the government did not fully disappear.[54] Paul

the Deacon gives an account of the Lombard tribal structure during the

migration:

. . . in order that they might increase the

number of their warriors, [the Lombards] confer liberty upon many whom they

deliver from the yoke of bondage, and that the freedom of these may be regarded

as established, they confirm it in their accustomed way by an arrow, uttering

certain words of their country in confirmation of the fact.

Complete emancipation appears to have been

granted only among the Franks and the Lombards.[55]

[edit]Society of the Catholic kingdom

See

also: Duke (Lombard)

Lombard society was divided into classes

comparable to those found in the other Germanic successor states of Rome: Frankish Gauland Visigothic Spain. There was a noble class, a class of

free persons beneath them, a class of unfree non-slaves (serfs), and finally

slaves. The aristocracy itself was poorer, more urbanised, and less landed than

elsewhere. Aside from the richest and most powerful of the dukes and the king

himself, Lombard noblemen tended to live in cities (unlike their Frankish

counterparts) and hold little more than twice as much in land as the merchant class

(a far cry from the provincial Frankish aristocrat who held a vast swathe of

land hundreds of times larger than the nearest man beneath him). The

aristocracy by the 8th century was highly dependent on the king for means of

income related especially to judicial duties: many Lombard nobles are referred

in contemporary documents as iudices (judges) even when their offices had

important military and legislative functions as well.

The freemen of the Lombard kingdom were far

more numerous than in Frankland, especially in the 8th century, when they are

almost invisible in the surviving documentary evidence for the latter.

Smallholders, owner-cultivators, and rentiers are the most numerous types of

person in surviving diplomata for the Lombard kingdom. They may have owned more

than half of the land in Lombard Italy. The freemen were exercitales and viri

devoti, that is, soldiers and "devoted men" (a military term like

"retainers"); they formed the levy of the Lombard army and they were, if

infrequently, sometimes called to serve, though this seems not to have been

their preference. The small landed class, however, lacked the political

influence necessary with the king (and the dukes) to control the politics and

legislation of the kingdom. The aristocracy was more thoroughly powerful

politically if not economically in Italy than in contemporary Gaul and Spain.

The urbanisation of Lombard Italy was

characterised by the città ad

isole (or "city as

islands"). It appears from archaeology that the great cities of Lombard

Italy — Pavia, Lucca, Siena, Arezzo, Milan — were themselves formed of very

minute islands of urbanisation within the old Roman city walls. The cities of

the Roman Empire had been partially destroyed in the series of wars of the 5th

and 6th centuries. Many sectors were left in ruins and ancient monuments became

fields of grass used as pastures for animals, thus the Roman Forumbecame the campo vaccinio: the field of

cows. The portions of the cities that remained intact were small and modest and

contained a cathedral or major church (often sumptuously decorated) and a few

public buildings and townhomes of the aristocracy. Few buildings of importance

were stone, most were wood. In the end, the inhabited parts of the cities were

separated from one another by stretches of pasture even within the city walls.

[edit]Lombard states

·

Lombard state on the Carpathians (6th

century)

·

Lombard state in Pannonia (6th century)

·

Kingdom of Italy and List of Kings of the

Lombards

·

Principality of

Benevento and List

of Dukes and Princes of Benevento

·

Principality of

Salerno and List of Princes

of Salerno

·

Principality of Capua and List of Princes of

Capua

[edit]Religious

history

[edit]Paganism

St. Barbatus of Benevento observed

many pagan rituals and traditions amongst the Lombards authorised by the Duke Romuald,

son ofKing Grimoald:[56]

"They expressed a religious

veneration to a golden viper, and prostrated themselves before it: they paid

also a superstitious honour to a tree, on which they hung the skin of a wild

beast, and these ceremonies were closed by public games, in which the skin

served for a mark at which bowmen shot arrows over their shoulder."

The earliest indications of Lombard religion

show that they originally worshipped the Germanic gods of the Vanir pantheon while in Scandinavia. After

settling along the Baltic coast, through contact with other Germans they

adopted the cult of the Aesir gods, a shift that represented a

cultural change from an agricultural society into a warrior society.[citation needed]

After their migration into Pannonia, the

Lombards had contact with the Iranian Sarmatians. From these people they borrowed a

long-lived custom once of religious symbolism. A long pole surmounted by the

figure of a bird, usually a dove, derived from the standards used in battle,

was placed by the family in the ground at the home of a man who had died far

afield in war and who could not be brought home for funeral and burial. Usually

the bird was oriented so as to point in the direction of the suspected site of

the warrior's death.[citation needed]

[edit]Christianisation

While still in Pannonia, the Lombards were

touched first by Christianity, but only touched: Their conversion and

Christianisation was largely nominal and far from complete. During the reign of Wacho,

they were Roman Catholics allied with the Byzantine Empire, butAlboin converted

to Arianism as

an ally of the Ostrogoths and

invaded Italy. All these Christian conversions affected, for the most part,

only the aristocracy, for the common people remained pagan.[citation needed]

In Italy, the Lombards were intensively

Christianised and the pressure to convert to Catholicism was great. With the

Bavarian queenTheodelinda, a

Catholic, the monarchy was brought under heavy Catholic influence. After an

initial support for the anti-Rome party in theSchism of the

Three Chapters, Theodelinda remained a close contact and supporter

of Pope Gregory I. In 603, Adaloald, the heir to the throne, received a

Catholic baptism. During the next century, Arianism and paganism continued to

hold out in Austria (the

northeast of Italy) and the Duchy of Benevento. A succession of Arian kings

were militarily aggressive and presented a threat to the Papacy in Rome. In the

7th century, the nominally Christian aristocracy of Benevento was still

practising pagan rituals, such as sacrifices in "sacred" woods. By

the end of the reign of Cunincpert, however, the Lombards were more or

less completely Catholicised. Under Liutprand,

the Catholicism became real[clarification

needed] as

the king sought to justify his title rex

totius Italiae by uniting the

south of the peninsula with the north and bringing together his Italo-Roman and

Germanic subjects into one Catholic state.

The Rule of Saint

Benedict in Beneventan

(i.e. Lombard) script

[edit]Beneventan Christianity

The Duchy and eventually Principality of

Benevento in southern Italy developed a unique Christian ritein

the 7th and 8th centuries. The Beneventan rite is more closely related to the

liturgy of theAmbrosian rite than the Roman rite. The Beneventan rite has not

survived in its complete form, although most of the principal feasts and several

feasts of local significance are extant. The Beneventan rite appears to have

been less complete, less systematic, and more liturgically flexible than the

Roman rite.

Characteristic of this rite was the Beneventan chant, a Lombard-influenced chant

that bore similarities to the Ambrosian chant of Lombard Milan. Beneventan chant is

largely defined by its role in the liturgy of the Beneventan rite; many

Beneventan chants were assigned multiple roles when inserted into Gregorian

chantbooks, appearing variously as antiphons, offertories, and communions, for

example. It was eventually supplanted by the Gregorian chant in the 11th century.

The chief centre of Beneventan chant was Montecassino, one of the first and greatest

abbeys ofWestern monasticism. Gisulf II of Benevento had donated a large swathe of land to

Montecassino in 744 and that became the basis for an important state, the Terra Sancti

Benedicti, which was a subject only to Rome. The Cassinese

influence on Christianity in southern Italy was immense. Montecassino was also

the starting point for another characteristic of Beneventan monasticism: the

use of the distinct Beneventan script, a clear, angular scrip

derived from the Roman cursive as used by the Lombards.

[edit]Art and architecture

During their nomadic phase, the Lombards

created little in the way of art that was not easily carried with them, like

arms and jewellery. Though relatively little of this has survived, it bears

resemblance to the similar endeavours of other Germanic tribes of northern and

central Europe from the same era.

The first major modifications to the Germanic

style of the Lombards came in Pannonia and especially in Italy, under the

influence of local,Byzantine,

and Christian styles. The conversions from nomadism

and paganism to settlement and Christianity also opened up new arenas of

artistic expression, such as architecture (especially churches) and its

accompanying decorative arts (such as frescoes).

Lombard shield boss

northern Italy, 7th Cen.Metropolitan Museum of Art

Lombard S-Fibula

A glass Drinking horn from Castel Trosino

Lombard Goldblattkreuz

Lombard Fibulae

Altar of Ratchis

[edit]Architecture

The Basilic autariana in Fara Gera d'Adda

Main

article: Lombard architecture

Few Lombard buildings have survived. Most

have been lost, rebuilt, or renovated at some point and so preserve little of

their original Lombard structure. Lombard architecture has been well-studied in

the 20th century, and Arthur Kingsley

Porter's four-volume Lombard

Architecture (1919) is a

"monument of illustrated history."

The small Oratorio di Santa Maria in Valle in Cividale del Friuli is probably one of the oldest

preserved pieces of Lombard architecture, as Cividale was the first Lombard

city in Italy. Parts of Lombard constructions have been preserved in Pavia (San Pietro in Ciel

d'Oro, crypts ofSant'Eusebio and San

Giovanni Domnarum) and Monza (cathedral).

The Basilic autariana in Fara Gera d'Adda near Bergamo and

the church of San Salvatore in Brescia also

have Lombard elements. All these building are in northern Italy (Langobardia

major), but by far the best-preserved Lombard structure is in southern Italy

(Langobardia minor). The Church of Santa

Sofia inBenevento was

erected in 760 by Duke Arechis II.

It preserves Lombard frescoes on the walls and even Lombard capitals on the

columns.

Through the impulse given by the Catholic

monarchs like Theodelinda, Liutprand,

and Desideriusto the foundation of monasteries to

further their political control, Lombard architecture flourished.Bobbio Abbey was

founded during this time.

Some of the late Lombard structures of the

9th and 10th century have been found to contain elements of style associated

withRomanesque

architecture and have

been so dubbed "first Romanesque".

These edifices are considered, along with some similar buildings in southern France and Catalonia, to mark a transitory phase between

the Pre-Romanesque and full-fledged Romanesque.

[edit]See also

·

Longobards in Italy, Places of Power (568-774 A.D.)

[edit]References

|

|

Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Lombards |

Notes

1.

^ a b Priester, 16. From the Old Germanic Winnan, meaning "fighting",

"winning".

2.

^ a b c d Harrison, D.; Svensson, K. (2007). Vikingaliv Fälth & Hässler, Värnamo. ISBN 978-91-27-35725-9 p. 74

3.

^ CG,

II.

4.

^ Menghin,

13.

5.

^ Priester, 16. Grimm, Deutsche Mythologie,

I, 336. Old

Germanic for "Strenuus",

"Sibyl".

6.

^ Priester,

16

7.

^ Hammerstein-Loxton,

56.

10.

^ OGL, appendix 11.

11.

^ Priester, 17

12.

^ PD, I, 9.

13.

^ Pohl and Erhart. Nedoma, 449–445.

14.

^ Priester, 17.

15.

^ Fröhlich, 19.

16.

^ Bruckner, 30–33.

18.

^ Strabo, VII, 1, 3. Menghin, 15.

19.

^ Wegewitz, Das langobardische Brandgräberfeld von

Putensen, Kreis Harburg (1972),

1–29. Problemi della civilita e dell'economia

Longobarda,

Milan (1964), 19ff.

20.

^ Menghin, 17.

21.

^ Menghin, 18.

22.

^ Priester, 18.

23.

^ Velleius, Hist. Rom. II, 106. Schmidt, 5.

24.

^ a b Tacitus, Ann. II, 45.

25.

^ Tacitus, Germania, 38-40; Tacitus, Annals,

II, 45.

26.

^ Tacitus, Annals, XI, 16, 17.

27.

^ Ptolemy, Geogr. II, 11, 9. Menghin, 15.

28.

^ Ptolemy, Geogr. II, 11, 17. Menghin, 15

29.

^ Codex Gothanus, II.

30.

^ Cassius Dio, 71, 3, 1. Menghin 16.

31.

^ Priester, 21. Zeuss, 471. Wiese, 38. Schmidt,

35–36.

32.

^ a b Priester, 14. Menghin, 16.

33.

^ Hartmann, II, pt I, 5.

34.

^ Menghin, 17, 19. Codex Gothanus, II.

35.

^ Zeuss, 471. Wiese, 38. Schmidt, 35–36.

Priester, 21–22. HGL, X.

36.

^ Hammerstein-Loxton, 56. Bluhme. HGL, XIII.

37.

^ Cosmographer of Ravenna, I, 11.

38.

^ Hodgkin, Ch. V, 92. HGL, XII.

39.

^ Schmidt, 49.

40.

^ Hodgkin, V, 143.

41.

^ Menghin, Das Reich an der Donau, 21.

42.

^ K. Priester, 22.

43.

^ Bluhme, Gens Langobardorum Bonn, 1868

44.

^ Menghin, 14.

45.

^ Hist. gentis Lang., Ch. XVII

46.

^ Hist. gentis Lang., Ch. XVII.

47.

^ PD, XVII.

48.

^ a b Peters, Edward (2003). History of the Lombards: Translated by

William Dudley Foulke.

University of Pennsylvania Press.

49.

^ "The New Cambridge Medieval History: c.

500-c. 700" by Paul Fouracre and Rosamond McKitterick (page 8)

50.

^ Lot, Ferdinand (1931). The End of the Ancient World and the

Beginnings of the Middle Ages. London.

51.

^ a b c Vidmar, Jernej. "Od kod prihajajo in kdo so solkanski Langobardi [From Where Come and

Who Are the Solkan Lombards]" (in Slovene). Retrieved 30 July 2012.

52.

^ Štih, Peter; Simoniti, Vasko; Vodopivec,

Peter (2008). "The

Settlement of the Slavs". In Lazarević, Žarko. A Slovene history: society - politics -

culture.

Ljubljana: Institute of Modern History. p. 22. ISBN 978-961-6386-19-7.

53.

^ Kortmann, Bernd (2011). The Languages and Linguistics of Europe:

Vol.II.

Berlin.

54.

^ Schmidt, 76–77.

55.

^ Schmidt, 47 n3.

56.

^ Rev. Butler, Alban (1866). The Lives of the Fathers, Martyrs, and Other

Principal Saints: Vol.I. London.

Bibliography

·

Cosmographer of Ravenna

·

Historia langobardorum

codicis Gothani

·

Historia Langobardorum

·

Origo gentis Langobardorum

·

Bluhme, Friedrich. Gens Langobardorum

·

Bruckner, Wilhelm. Die Sprache der Langobarden

·

Christie,

Neil (1995). The Lombards: the ancient Longobards. The Peoples of Europe. Oxford: Blackwell.

·

Everett,

Nicholas (2003). Literacy in Lombard Italy, C. 568-774. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press. ISBN 0-521-81905-9, 9780521819053.

·

Fröhlich, Harmann. Studien zur langobardischen

Thronfolge - Zur Herkunft der Langobarden -

Quellen und Forschungen aus italienischen Archiven und Bibliotheken (QFIAB)

·

Giess, Hildegard. "The Sculpture of the Cloister of Santa Sofia in

Benevento",The Art Bulletin, Vol. 41, No. 3. (September

1959), pp 249–256.

·

Grimm. Deutsche

Mythologie

·

Gwatkin, H. M., Whitney, J. P. (ed) - The Cambridge Medieval History:

Volume II—The Rise of the Saracens and the Foundations of the Western Empire.

Cambridge University Press, 1926.

·

Hallenbeck, Jan T. "Pavia and

Rome: The Lombard Monarchy and the Papacy in the Eighth Century" Transactions of the American

Philosophical Society New

Series, 72.4 (1982),

pp. 1–186.

·

Hammerstein-Loxten, Freiherren von. Bardengau

·

Hartmann, Ludo Moritz. Geschichte Italiens im Mittelalter

II Vol.

·

Hodgkin, Thomas. Italy and her Invaders. Clarendon Press

·

Menghin, Wilifred. Die Langobarden / Geschichte und

Archäologie. Theiss

·

Oman, Charles. The Dark Ages 476-918. London,

1914.

·

Pohl, Walter and Erhart, Peter. Die Langobarden / Herrschaft und

Identität

·

Priester, Karin. Geschichte der Langobarden /

Gesellschaft - Kultur - Altagsleben. Theiss

·

Rothair;

Grimwald; Liutprand; Ratchis; Aistulf; Katherine Fischer

Drew (Translator, Editor); Edward Peters (Foreword) (1973). The Lombard Laws. Philadelphia: University

of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-1055-7.

·

Santosuosso, Antonio. Barbarians, Marauders, and

Infidels: The Ways of Medieval Warfare. 2004. ISBN 0-8133-9153-9

·

Schmidt, Dr. Ludwig. Älteste Geschichte der Langobarden

·

Tacitus. Annals

·

Tacitus. Germania

·

Wegewitz, Willi. Das Langobardische brandgräberfeld

von Putensen, Kreise Harburg

·

Wickham, Christopher (1998). "Aristocratic Power in

Eighth-Century Lombard Italy". In Goffart, Walter A.; Murray, Alexander

C.. After Rome's Fall: Narrators and Sources of

Early Medieval History, Essays presented to Walter Goffart. Toronto: University of

Toronto Press. pp. 153–170. ISBN 0-8020-0779-1.

·

Wiese, Rbert Die aelteste Geschichte der

Langobarden

·

Zeuss, Kaspar. Die Deutschen und die Nachbarstämme

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LXrrcZWvuAY

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y5a4V5fy_kQ

Vocabulaire d'Anglais

Leçon d'Anglais Gratuite par Email. Apprenez l'Anglais 5

mins par Jour.

Englishtown.com/Anglais-Gratuit

Lombards (lŏm`bərdz,

–bärdz), ancient Germanic people. By

the 1st cent. A.D. the

The

Bibliography

See T. Hodgkin, Italy and Her Invaders, Vol. V and VI (1895, repr. 1967); P.

Villari, Barbarian Invasions

of Italy (2 vol., tr. 1902);

J. T. Hallenbeck, Pavia and

Rome: The Lombard Monarchy and the Papacy in the Eighth Century (1982).

The

Kerala, God's Own Country

Explore Serene Beaches, Backwaters, Hill Stations &

Exotic Wildlife!

www.keralatourism.org

Warning! The following article is from The

Great Soviet Encyclopedia (1979). It might be outdated or ideologically biased.

Lombards

a Germanic tribe.

In the first century A.D. the

In the late sixth to

mid-seventh centuries the

By the mid-eighth

century royal authority under the Lombards had weakened. An effort by Liudprand

and Aistulf to draw support from the Catholic clergy also failed to strengthen

their power. The Lombards’ expansionist policy (seizure of Ravenna in 751 and

an attempt to capture Rome) ended in failure, which to a certain extent was

caused by the intervention of the Franks, who were in alliance with the papacy.

In 773–774, under Desiderius (reigned in 756–774), the kingdom of the Lombards

was conquered by Charlemagne.

REFERENCE

Istorila

Italii, vol. 1. Moscow, 1970. (Contains a

bibliography.)

L. A. KOTEL’NIKOVA

. LANGOBARDS, HEAÐOBARDS

AND DANES

Before you read this

post you should read my post about the Proto-Germanic people:

http://www.keyoghettson.com/2010/11/proto-germanic-people_30.html

The Langobards and

the Heaðobards were probably the same people. I think Skåne was the original

homeland of the Langobards. Origo Gentis Langobardorum (7th century) and

Historia Langobardorum (8th century) tell the history of the Langobards.

According to these texts the Langobards were originally called Winnili and

their original homeland was called Scadan/Scadanan. According to Historia

Langobardorum the Winnili split into three groups. One of the groups left their

original homeland. This group would later become the Langobards. I think the

Heaðobards were the Winnili that remained.

This is how Scadan/Scadanan is described in Historia Langobardorum:

This island then, as those who have examined it have related to us, is not so

much placed in the sea as it is washed about by the sea waves which encompass

the land on account of the flatness of the shores.

According to ancient writers the Langobards dwelt near the mouth of the river

Elbe at the beginning of the Common Era. The place-names Bardengau and Bardowick

in what today is northern Germany most likely derive from the name of the

Langobards. It can hardly be said of neither Bardengau or Bardowick that it is

surrounded by sea waves. Skåne on the other hand fit the description very well.

In ancient texts Scandinavia is refered to as an island. Skåne (aka Scania) and

Scandinavia have the same etymology. It's two different forms of the same name.

Originally it was the name for Skåne. Later it became the name for all of

Scandinavia. The Old Norse name for Skåne was Skáney. The second segment of

Skáney means island. The Old English name for Skåne was Scedenig. The second

segment of the name represents Old English īġ that means island. Note

the similarity between Scadan/Scadanan and Scedenig.

Beowulf (8th century) is an Old English poem. The text mention a feud between

the Danes and the Heaðobards. According to the text the Danes killed the

Heaðobard king Froda. The Danish king sent his daughter to marry Froda's son

Ingeld to end the feud. One of the Heaðobards urged the other Heaðobards to

avenge Froda. Widsith (9th century) is another Old English poem. The text also

mentions the feud between the Danes and the Heaðobards. According to the text

the Danes defeated the Heaðobards. In later Scandinavian texts Froda is

referred to as a Danish king. The later Scandinavian texts mention the feud but

not the Heaðobards. The Heaðobards had either been forgotten by then

or the Heaðobards were deliberately erased from history by the the Danes. Froda

was not a Danish king. Froda was a Heaðobard king.

The Heaðobard that urged the other Heaðobards to avenge Froda was